The Mythmakers

John Hendrix, the gifted author and illustrator of The Faithful Spy, is back with another graphic biography in the same vein, called The Mythmakers: The Remarkable Fellowship of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien (Abrams Fanfare).

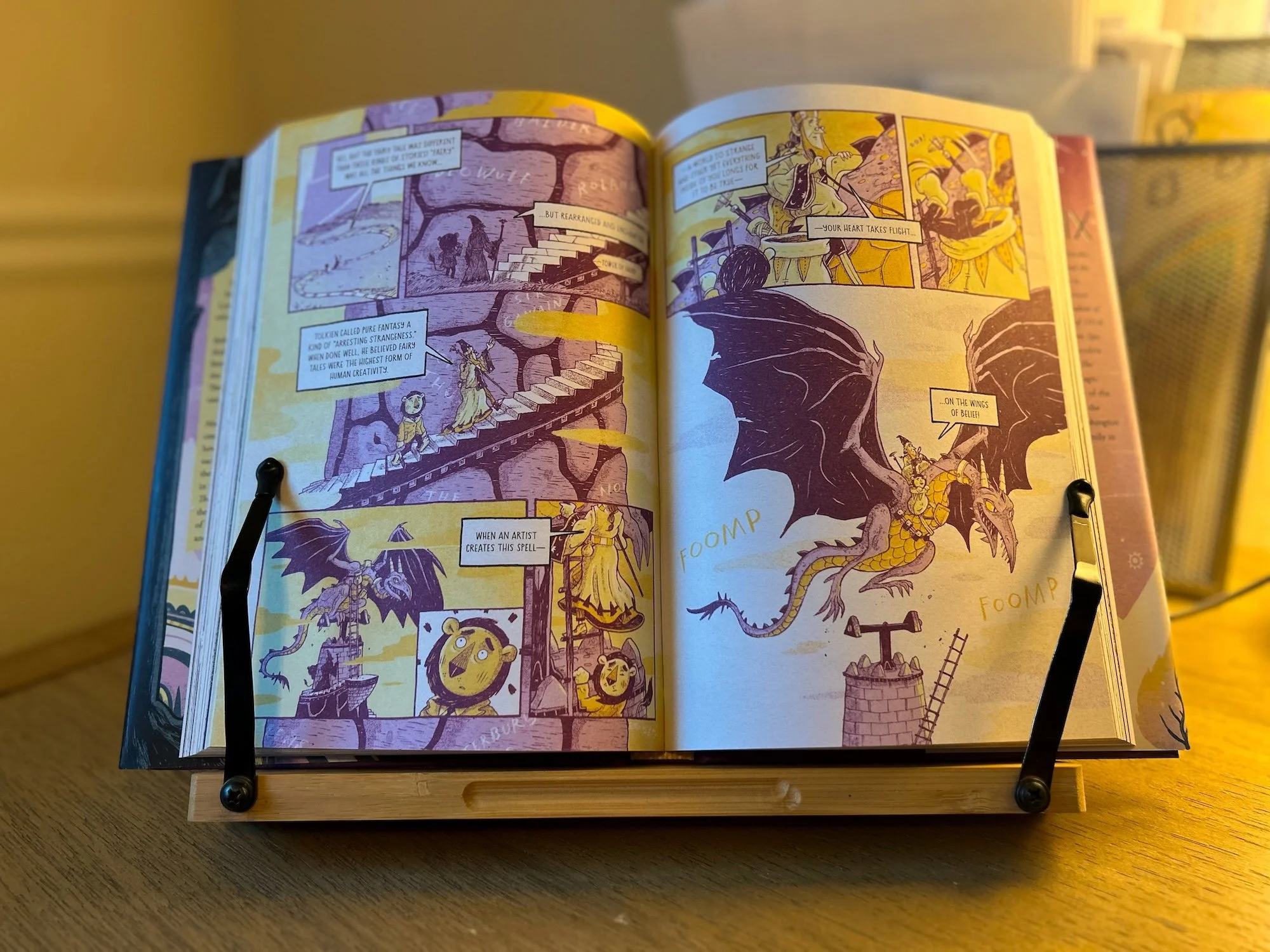

Weaving together the stories of the two most famous Inklings who gave us The Chronicles of Narnia and The Lord of the Rings, Hendrix is particularly interested in the myths and “faery stories” that fascinated and energized them, beginning with the Norse mythology they devoured in their formative years.

Hendrix traces their shared interest in “world-building” to their childhoods, when Tolkien and Lewis suffered the losses of parents, as well as the traumas both endured during World War I. “War is always a vastly dehumanizing experience,” Hendrix writes, “but the Great War profoundly broke the souls of men.”

Lewis, for his part, returned from the front line bearing two injuries: “A splinter of shrapnel was lodged near his heart, but the true wound Lewis carried was the fear that his deepest longings for joy were lies.” It would be more than a decade until his conversion—“the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England,” as he memorably put it. But a wrestling with myth was a at the heart of the search. Hendrix writes, “To accept the truth of Christianity, Jack didn’t have to believe that all the other myths in the world that he loved were wrong. He simply had to believe in the fulfillment of myth. It was the key that opened the door to the rest of his life.”

Tolkien, a Roman Catholic, was faithful in accompanying his literary friend in the spiritual quest, though Lewis would make his home in the Church of England—eventually becoming one of the most recognizable Anglican figures in history, despite never being ordained.

Their friendship, however, was not uncomplicated. Tolkien never liked Lewis’s predilection, as a layman, to write and lecture on theological themes. As they wrote their respective masterpieces, they didn’t always appreciate what the other was doing. Despite everything the two “mythmakers” had in common, over time their bond began to fray until the Inklings, as a group of “like-minded friends,” simply ceased to exist.

It’s a sad end to an otherwise enchanted tale. What writer among us hasn’t dreamed of being part of our very own gang of Inklings? Who of us hasn’t longed for that kind of literary friendship—in a pub with a pint, no less?

In the closing pages Hendrix writes, “To Tolkien and Lewis, the imagination was not a vehicle for escapism or shoddy entertainment, but humankind’s true ‘organ of meaning.’ For many, myself included, encountering their works felt like that astonishing realization in anyone’s life, as Lewis said, that ‘there do exist people very, very like himself.’”

Thanks be to God for our fellow travelers, these meaning-making friends. Thanks too for books like this, reminding us that while reading stories can be a magical experience—transporting us to a “time out of time” and a “place out of place”—the writing itself is almost always an unromantic slog.

As Hendrix himself puts it, “Great stories are written on a normal Tuesday afternoon.”