Chasing Me to My Grave

In these days of chaos and cruelty by decree, I’ve been looking for ways to stay human—strategies for resisting the outrage machine, practices for keeping a clear mind and a tender heart. Here are a few:

Morning and evening prayer. Daily work in service of families deemed disposable (or worse) by men with atrophied imaginations. Long walks with Katie. Sabbath feasts. Messages to check in on those who are afraid. Visits to the art museum. An Ethiopian coffee ceremony, of all things. Poetry. Fiction. Film.

As another act of resistance and hope, at our local bookstore I picked up Chasing Me to My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir of the Jim Crow South (Bloomsbury) by the late Winfred Rembert, as told to the Tufts philosopher Erin I. Kelly. This is a memoir, yes: Rembert’s story is horrifying if ultimately hopeful. But it’s also a coffee table book replete with Rembert’s stunning paintings, originally composed on leather.

In his foreword, Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative writes about seeing Rembert’s work for the first time as part of an exhibition at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in September 2013. “On that Sunday,” Stevenson recalls, “Mr. Rembert’s art converted a conventional, quiet museum in Montgomery into something that felt like a dynamic Black church: a place of confession and repentance leading to redemption and salvation.”

Rembert credits his wife Patsy with the idea of creating a record of his experiences on leather. At first, the suggestion struck him as wild. Gradually, though, he came around. “I was doing something that had never been done by an artist—to preserve his life on leather,” he writes. “On leather—not paper—leather, something that will not deteriorate. . . . Show me someone who is doing a picture, a picture, on leather, about their life. I was doing something no one else was doing and I was happy about that. I was real happy about that.”

To create a new work of art, Rembert would take a piece of leather and spray it with water to soften it. “The water won’t hurt it,” he assures us. “You could throw a piece of leather in the bathtub and let it stay all night.” Next, he’d cut the leather into a canvas. The final stage before painting was to bevel the leather, creating grooves that would give the final image its “3-D look.” Rembert writes:

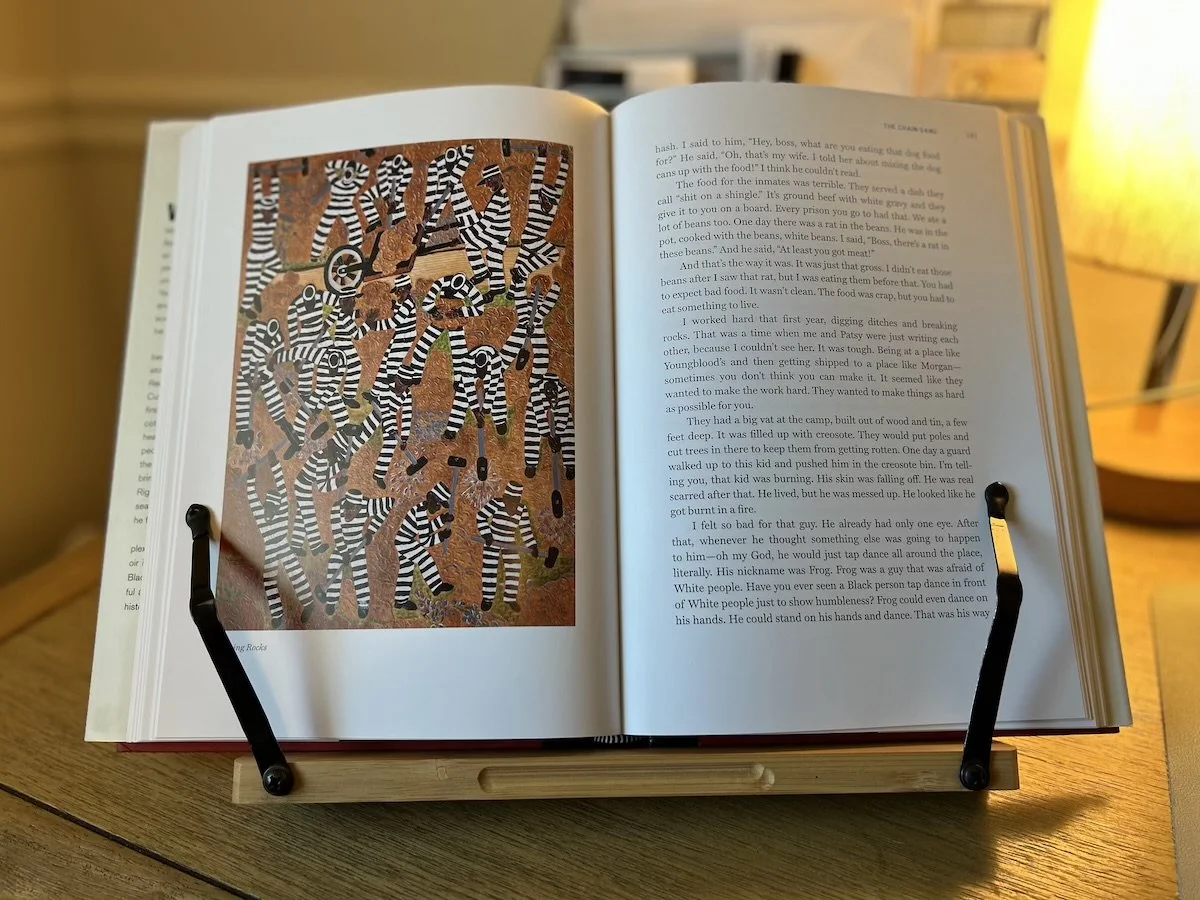

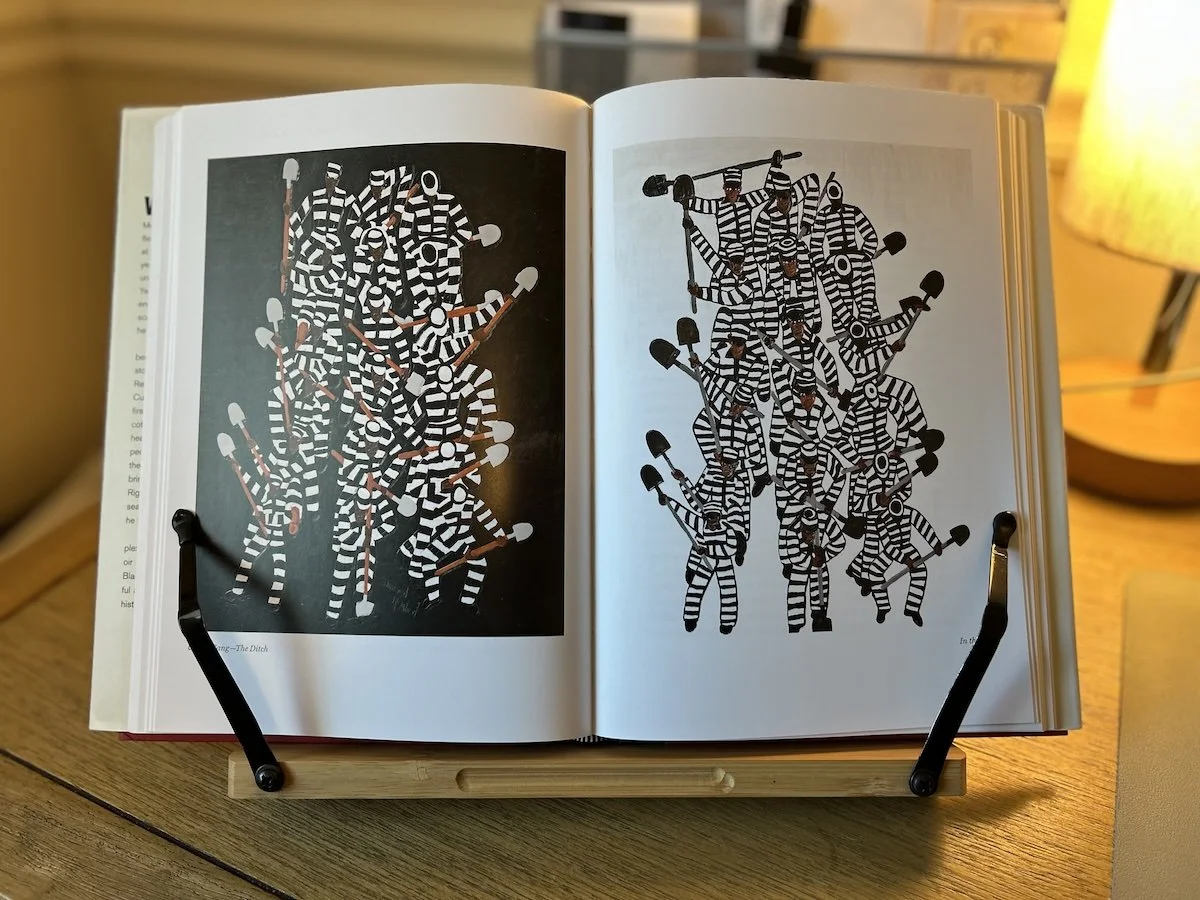

“My pictures are carved and painted on leather, using skills I learned in prison. Leather takes a beating, and whatever you do with it, it will hold its shape. You can carve it up and it will hold your picture. My pictures tell about cotton plantations, Jim Crow, the civil rights movement, and my time as a prisoner. They celebrate the people I knew and loved and how they lived. These are my memories of Black life in the 1950s and 1960s, and how those of us who left the South took it with us and kept it. I want to share my memories with people who lived through what I lived through. . . . I want Black people to be proud of what their families sacrificed and how they survived. I want people who have lived in the South to talk about their history.”

Among the paintings reproduced in this book are scenes depicting life as sharecroppers in cotton fields; mistreatment at the hands of the police; Black-owned businesses buzzing with activity; lynchings and near-lynchings; prison life; Black joy in song and dance and sport; portraits of loved ones; exuberant worship; chain gangs. He writes:

“With my paintings, I tried to make a bad situation look good. You can’t make the chain gang look good in any way besides putting it in art. Those black and white stripes look good on canvas. People can’t really tell what they are until they get up close. They don’t recognize those stripes as people until they take a real good look. That was my goal—to put it down so you couldn’t understand it until you take a real up-close look. That tells you something about prison life. When you look at it from the outside you can’t see what’s going on, but when you’re up close you realize what you’re up against.”

One of the gifts we receive from art, it seems to me, is the possibility of remaining open to surprise. This too is a strategy to resist the hardening of our hearts. Perhaps especially in those moments, as Stevenson puts it, “when the world desperately needs more beautiful things to discover and cherish.”