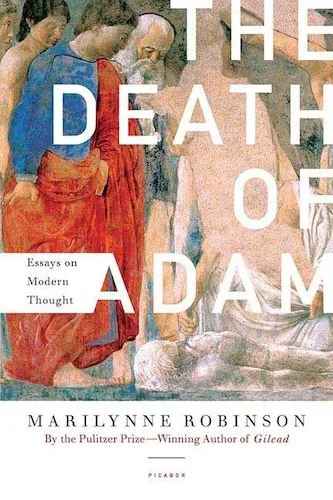

The Death of Adam

No one writes essays quite the way Marilynne Robinson writes essays.

If you’ve read her nonfiction you probably know what I mean, but there’s this thing she does in her commentary on culture and religion—on contemporary moods and frames of mind, especially—where she starts a few miles upstream from where it would occur to you or me to dive in. Time and again she sends us back to the headwaters of historical precedent and primary source material. It’s as if she is warning us: we will fail to navigate our present bend in the river if we misunderstand all the bends that have come before.

Robinson published The Death of Adam: Essays on Modern Thought (Picador) more than 25 years ago. But because of her careful attention to the headwaters, insights into the travails and psychoses of the ‘90s feel relevant today, in a world changed (it would seem) almost beyond recognition.

There’s an essay on Darwinism, a “chilling doctrine,” one “harsh and crude in its practical consequences”—and one on full display in our daily lives. Implicit in the idea of the survival of the fittest, Robinson writes, is a worldview “too small and rigid to accommodate anything remotely like the world.” Uncoincidentally, she continues, “it had its origins in polemics against the poor, and against the irksome burden of extending charity to them.”

In other essays, Robinson reconsiders the legacies of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and John Calvin and the Puritans, seeking to rescue them, each in their own way, from those who’ve never bothered to read them—or never read them in context—but hold strong opinions anyway.

I appreciate and find instructive the way Robinson names where she’s coming from, some of the headwaters of her own life and work. For one thing, she owns her politics: “I am myself a liberal. By that I mean I believe society exists to nurture and liberate the human spirit, and that large-mindedness and openhandedness are the means by which these things are to be accomplished.” She continues with a vital distinction: “I am not ideological. By that I mean I believe opportunities of every kind should be seized upon to advance the well-being of people, especially in assuring them decent wages, free time, privacy, education, and health care, concerns essential to their full enfranchisement.”

Robinson also writes, unambiguously, as a Christian—a mainline Protestant (“a.k.a. liberal Protestant”) of the Calvinist and Congregationalist variety. “I have a strong attachment to the Scriptures, and to the theology, music, and art Christianity has inspired,” she says. “My most inward thoughts and ponderings are formed by the narratives and traditions of Christianity. I expect them to engage me on my deathbed. . . . I do not by any means wear my religion on my sleeve. I am extremely reluctant to talk about it at all, chiefly because my belief does not readily reduce itself to simple statements.”

I relate to that last bit about the irreducibility of belief to sound-bites, and how it may be preferable, in certain circumstances, to leave the most important things (momentarily) unsaid. Perhaps that’s why I was especially moved by her essay on the personal significance of Psalm 8 in her life as a young girl, at a time when members of her family “would not have known, because no one knew, that I was becoming a pious child.” She writes:

“What this meant precisely, and why it was true, I can only speculate. But it seems to me I felt God as a presence before I had a name for him, and long before I knew words like ‘faith’ or ‘belief.’ I was aware to the point of alarm of a vast energy of intention, all around me, barely restrained, and I thought everyone else must be aware of it. For that reason I found the majestic terrains of my childhood, to which my ancestors had brought their ornate Victorian appreciation at daunting cost in life and limb, very disturbing, and I averted my gaze as I could from all these luminist splendors. I was coaxed to admire, and I would not, admiration seeming so poor a thing in the circumstances. Only in church did I hear experience like mine acknowledged, in all those strange narratives, read and expounded and, for all that, opaque as figures of angels painted on gold.”