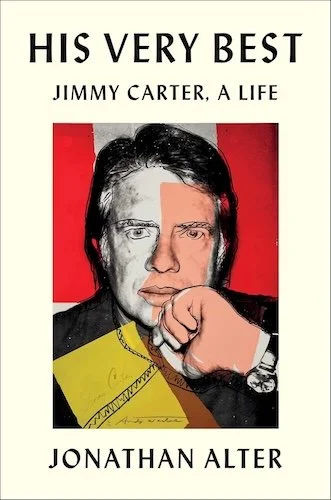

His Very Best

Jimmy Carter’s single term in the White House preceded my time on Earth. Sandwiched between Watergate and Reaganomics, his presidency is mostly known for stagflation, the Iran hostage crisis, and the “malaise” speech. In his post-presidency, though, Carter’s name became synonymous with conflict mediation, free and fair elections, disease eradication, and Habitat for Humanity house-builds, including the one with the black eye.

If you’re like me, it will seem like an uncontroversial assessment: in later life, Carter was an inspiring, world-changing humanitarian; as president, he was mediocre at best.

In the hefty 2021 biography His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life (Simon & Schuster), the journalist Jonathan Alter complicates the narrative. He argues the enigmatic Carter was “a surprisingly consequential president—a political and stylistic failure but a substantive and far-sighted success,” while concluding that “his postpresidency—while pathbreaking and inspiring—offered him fewer levers for change and was marred at times by his ego and is thus a bit overrated.”

It’s been nearly two years since I read the book, so I won’t try to break it all down. But there’s one piece of the story that stood out to me then, and has renewed salience right now, for reasons unrelated to Carter’s passing but not unrelated to the presidency itself.

Alter confirms what is widely agreed: Carter was a man of integrity, with basic decency at his core. But he also suggests Carter’s career suffered, ultimately leading to his reelection loss, because he was constitutionally—that is, both morally and temperamentally—opposed to political expediency.

The paradoxes of Carter’s legacy in a nutshell: In 1977 and 1978, Carter successfully negotiated the Panama Canal treaties, giving Panama eventual control of the Canal Zone. Ratification required a two-thirds vote in the US Senate, which Carter was painstakingly able to secure despite the unpopularity of the treaties with the electorate. Throughout the 1970s and during his run against Carter in 1980, Ronald Reagan had campaigned against the treaties, and won in part because of his position on it. But then it came time to govern, at which point realism and responsibility set in. Alter writes:

“After Reagan was elected, William F. Buckley wrote that Reagan won by losing on Panama. If he had supported the treaties, he would never have been nominated in 1980. But if he had successfully defeated them, there would have been an insurrection in Panama, and, proven wrong about the deadly consequences of rejecting the treaties, he would not have beaten Carter. Upon taking office in 1981, Reagan didn’t touch the treaties he had railed against. He privately considered them a ‘success story’ that required no modification, much less abrogation. But he refused to admit he had been wrong in his career-making opposition.”

Alter continues:

“The Panama Canal victory nonetheless testified to the power and occasional virtue of elites, who—as the founders understood—can sometimes offer a cooling saucer for the heat of public opinion. Ratification of the treaties was clearly in the national interest of the United States, as even most opponents admitted later. And for all of Jimmy Carter’s grousing about how ‘horrible’ it was to entertain members of Congress night after night, he was perfectly cast for the thankless but historic task of securing ratification. His speechwriter Rick Hertzberg saw it as the quintessential Carter achievement, one that rewarded his hard work, offered no political dividends, and drew on an alleged personal liability that was actually more often an asset.”

Jimmy Carter, America’s “born-again” president, made a habit of taking the long view, eschewing if necessary short-term gains. There’s wisdom in that. And more often than not, personal costs.

Carter will be eulogized at the National Cathedral this morning, and buried back home in Plains, Georgia, right around dusk.