Storytelling and Ethics

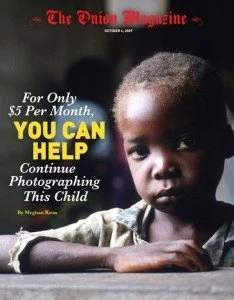

Last night I tweeted this from The Onion, saying: “Let’s admit it, NGO marketing/comms folks… we kinda had this one coming.”

As someone working in the field of relief and development, I wrestle with the ways NGOs represent their work and the ways we go about getting funding to keep that work going. Do the very noble ends (serving the poor, saving lives) really justify the often less noble means? Do vivid photos of starving children really serve anyone? Do mass mailings that most people just throw in the trash justify the cost of production, both as a percentage of donor money and in terms of environmental degradation, something that has a devastating effect on the very poor these organizations purport to serve? Those are just a couple of the questions I wrestle with.

In regard to the first question, about the ethics of using emotionally compelling but ethically troubling images, I’m grateful for the work of the International Guild of Visual Peacemakers, a group of photographers and videographers “devoted to peacemaking and breaking down stereotypes by displaying the beauty and dignity of various cultures around the world.” For those producing visual content, they offer an ethical code. And for those of us who consume visual content (all of us), they invite us to sign a charter for visual peace. The creative, talented, compassionate folks at IGVP are doing important work that I hope will continue to shape how NGOs, businesses, and independent communicators reflect the dignity of their subjects.

Within the faith-based sector, which is more narrowly where I happen to work, we’re not immune to these ethical concerns. If anything, we need to be extra vigilant, given the way spiritual guilt can so easily be used to manipulate. I’ve been reflecting on these things for a while now, but just this morning while eating breakfast and reading The Knowledge of the Holy by A.W. Tozer, I came across this passage that brings the matter home for us in theological terms. His language is a bit old-fashioned, and he refers specifically to “missionary appeals,” but what he says is true of faith-based humanitarian and social justice pleas as well:

Probably the hardest thought of all for our natural egotism to entertain is that God does not need our help. We commonly represent Him as a busy, eager, somewhat frustrated Father hurrying about seeking help to carry out His benevolent plan to bring peace and salvation to the world, but, as said the Lady Julian, “I saw truly that God doeth all-thing, be it never so little.” The God who worketh all things surely needs no help and no helpers.

Too many missionary appeals are based upon this fancied frustration of Almighty God. An effective speaker can easily excite pity in his hearers, not only for the heathen but for the God who has tried so hard and so long to save them and has failed for want of support. I fear that thousands of younger persons enter Christian service from no higher motive than to help deliver God from the embarrassing situation His love has gotten Him into and His limited abilities seem unable to get Him out of. Add to this a certain degree of commendable idealism and a fair amount of compassion for the underprivileged and you have the true drive behind much Christian activity today.

The key word in that passage, I think, is need. God does not need our help. He invites us to join him in his work, and we do so in response to the love and grace we have received. When we pray, “Your kingdom come, your will be done on earth as it is in heaven,” we may find him moving us to act accordingly. But guilt won’t do it. It won’t last. Rather, we can serve the poor with a quiet trust in a loving God, a God who will do his thing whether we’re part of it or not.

Be still, and know that I am God. I will be exalted among the nations, I will be exalted in the earth! (Ps 46:10)

What would our marketing look like if we believed that?