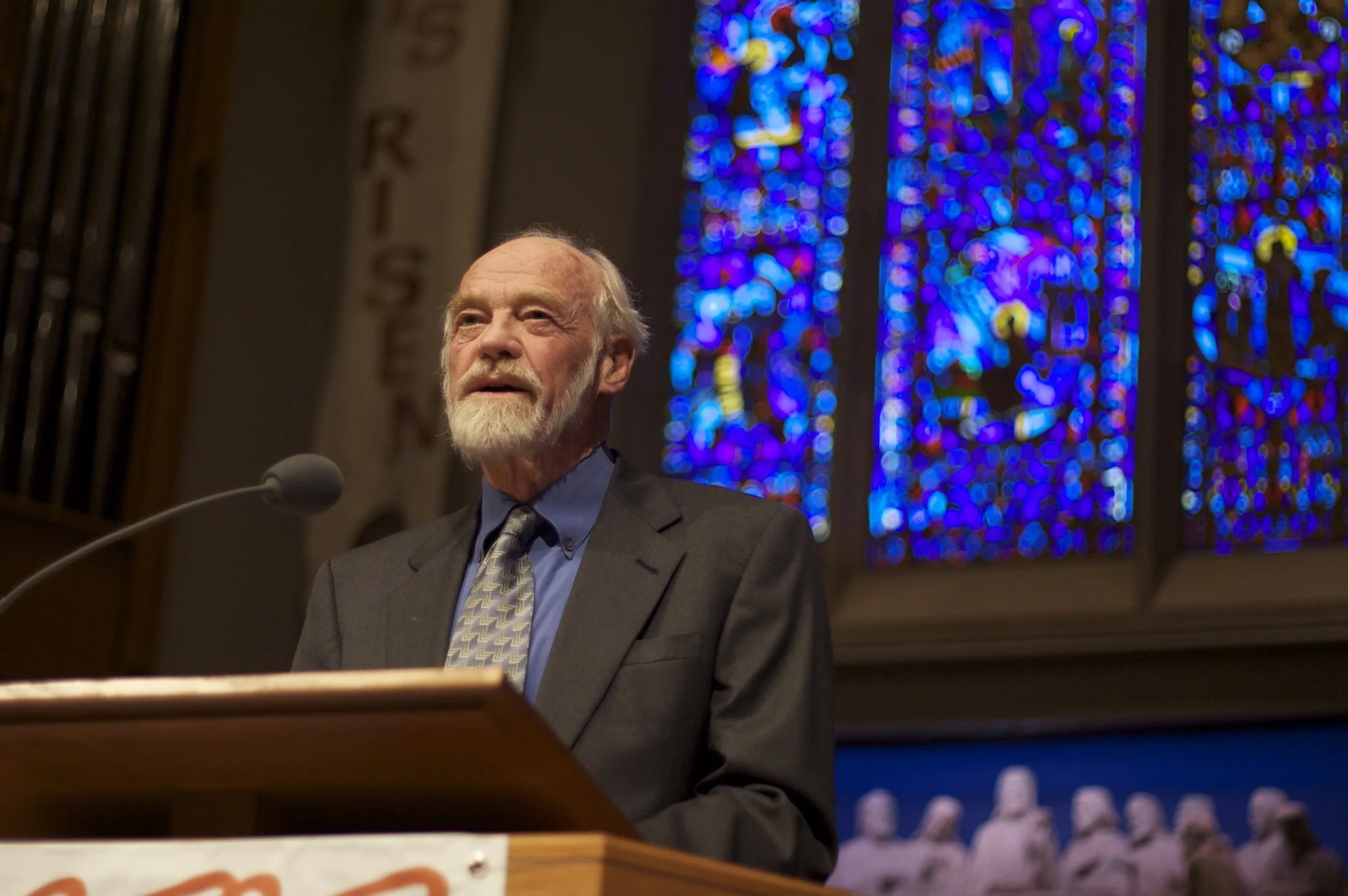

Eugene H. Peterson, My Relative

I’ve long been a fan of Eugene H. Peterson. Most people know him as “The Message guy,” for better or worse, but for decades he’s been writing rich, stirring books on what he calls “spiritual theology.” A Long Obedience in the Same Direction, a book on Christian discipleship with a title re-appropriated from Nietzsche, of all people, is one worth reading again and again. That’s just one of some 30 books he’s written.

But it was his work as a pastor in suburban Baltimore for nearly 30 years that has defined his life vocationally. That’s the subject of his new book, The Pastor: A Memoir. It’s a wonderful book for anyone who is a pastor, has a pastor, or has opinions about pastors. That’s most of us.

Peterson’s writing is what endeared him to me in the first place, but I must admit there was an added element of intrigue when I discovered that Eugene H. Peterson’s middle name is Hoiland. Then I learned that he was born in Stanwood, Washington, a small town where my grandfather Theol Hoiland served as a Lutheran pastor and where my dad lived for a bit as a kid. And now, Peterson’s memoir reveals some of the branches in our shared family tree. Though Peterson’s father was Swedish, his mother was Norwegian, and her maiden name was Hoiland. Her parents, Eugene’s maternal grandparents, arrived in the United States in the early 1900s, coming from Stavanger, the part of Norway where my ancestors also originated.

The Hoilands of Stavanger: Eugene’s ancestors and mine.

So what specifically does Peterson have to say about these Hoilands? Well, he refers to two of them in detail: his grandfather Andre and his uncle Sven. Andre came to the US by himself in 1900 to work in a steel mill in Pittsburgh, before returning to get his wife and nine kids and bring them to settle in Montana, where he found work making sidewalks. Legend has it that when the Hoilands settled in Montana, they brought with them a Norwegian troll named Skogen. A bit odd, I know. But not as strange as the story of Sven, one of Andre’s sons and Eugene’s mother’s favorite older brother. Sven, as it happens, was shot and killed by his wife after he beat her and told her to solicit herself. He was a drunk, an adulterer, and a thief — and had been married a mere six weeks.

Peterson heard these stories — good ones from his mother, bad ones from everyone else — and wondered what to make of it all. But as he reflected back on those stories, he realized that the complicated legacy of Uncle Sven helped form him as the pastor he would eventually become:

The contradictions in Sven, the affectionate and playful big brother set alongside the abusive and violent husband, worked themselves into my adolescent imagination. Did one cancel the other? Was there any way to get the playful brother and the abusive husband into the same story?

At some point he set out to write a novel based on the complex character of Sven, though it never amounted to much:

But the effort to accommodate the ambiguities of the moral and spiritual life did. I had no idea as I was plotting this novel that I was developing a pastoral imagination adequate for entering into the complexities of good and evil, sin and salvation, that make up much of the daily life of a congregation. When I finally did become a pastor, I was surprised at how thoroughly Sven had inoculated me against “one answer” systems of spiritual care: “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple and wrong” is the warning posted by H.L. Mencken.

Thanks to Sven, I was being prepared to understand a congregation as a gathering of people that requires a context as large as the Bible itself if we are to deal with the ambiguities of life in the actual circumstances in which people live them. If the life of David that comprised prayer and adultery and murder could be written and told as a gospel story, no one in my congregation would be written off. For me, my congregation would become a work-in-progress — a novel in which everyone and everything is connected in a salvation story in which Jesus has the last word. No reductions to stereotype: not my grandmother’s desperate reduction of her son to a death-bed repentance, not my mother’s affectionate reduction of her brother to a fun-loving, devil-may-care naif, not the jury’s legal reduction of Sven to a drunken wife abuser, not the detached reduction by a psychiatrist of Sven to a narcissistic sociopath.

I’m proud to be related to Eugene Hoiland Peterson. I’m not proud to be related to Sven. But like it or not, I’m related to both. One way or another, so are you.