Samuel Escobar: Freedom & Justice (The Lausanne Series, Part 2)

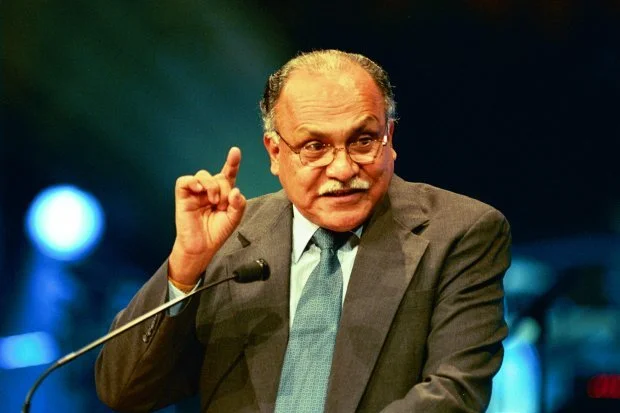

Last week, in the first part of this series on the Lausanne Movement and what it has to teach us about faith, development, justice and peace, we took a look at René Padilla’s presentation. Now we turn to Peruvian theologian Samuel Escobar, whose theme is “Evangelization and Man’s Search for Freedom, Justice, and Fulfillment.”

Samuel Escobar begins his presentation by appealing to the decision made by the organizers of the gathering to choose as a motto the words of Jesus in the synagogue, found in Luke 4:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.

He then urges his listeners to take these words seriously, which is to say, not to overly spiritualize the message. In a world with millions suffering from literal poverty, captivity, blindness and oppression, these words aren’t just about spiritual poverty or captivity to sin. There are a lot of Christians in the world, Escobar says, who take these words seriously, and they find themselves in far flung corners of the world and near centers of power, following Christ accordingly. But many of them face strong pressure from other Christians, of all people, to change course:

Some of them have been criticized and told that they should abandon their efforts for the pursuit only of numerical growth of congregations. I hope they will not believe that such is the official position of the [Lausanne] Congress.

As we saw last week, Padilla also critiqued the pursuit of numerical growth as an end in itself, represented most clearly in the church growth movement that has given rise to many of the megachurches across the country and around the world. Escobar was warning against numerical growth at the expense of discipleship, creating a “consumer class” of Christians who were uninterested in the personal and social implications of submitting to the Lordship of Christ. He saw discipleship as essential, and he saw churches as the indispensable communities where discipleship happens:

I think that the first and powerful answer to the social and political needs of men, to the search for freedom, justice, and fulfillment, is given by Jesus in his own work and in the church… [In the church] Jesus creates a new people, a new community where these problems are dealt with under the Lordship of Christ.

What he was calling for may have cut across the grain of many at that time, but it was really nothing new for evangelicals. He pointed to John Wesley, the well-known evangelist who authored a book called Thoughts upon Slavery, calling for abolition long before it became reality, and long before it was a popular idea. For Wesley, evangelism and social issues like slavery belonged hand in hand:

In today’s language, we could say that for Wesley, development without social justice was unacceptable. I pray that God will raise in this Congress evangelists like Wesley, who also care about social evils enough as to do research and write about them and throw the weight of their moral and spiritual authority on the side of the correction of injustices. Wesley, however, did more than writing. He encouraged the political action that eventually was going to abolish slavery in England.

Shortly before he died, Wesley wrote to William Wilberforce, urging him to use his political position to push for the abolition of slavery, something Wilberforce eventually succeeded in doing, giving us a powerful example to follow. But while evangelicals have every reason to stand with the oppressed, we must remember that political liberation and the freedom offered in the gospel are two distinct things, Escobar says:

Simple liberation from human masters is not the freedom of which the Gospel speaks. Freedom in Christian terms means subjection to Jesus Christ as Lord, deliverance from bondage to sin and Satan… However, the heart which has been made free with the freedom of Christ cannot be indifferent to the human longings for deliverance from economic, political, or social oppression.

Escobar points also to a contemporary evangelical leader who recognized this connection: world-famous evangelist Billy Graham, who made it his policy to refuse to speak to segregated audiences. As you can imagine, this was quite an unpopular move with many in his “target market” at the time:

He did not downgrade the demands of the Gospel in order to have access to a greater number of hearers or in order to have the blessing of racists that would consider themselves ‘fundamental Christians.’ A stance like this is already communicating something about the nature of the Gospel that gives credibility to the Gospel itself when it is announced… To perpetuate segregation for the sake of numerical growth, arguing that segregated churches grow faster, is for me yielding to the sinfulness or society, refusing to show a new and unique way of life.

Escobar has a lot more to say than what I’ve mentioned here, and just like Padilla’s message, it’s all as timely as ever. He finishes on an eschatological high note:

We reaffirm our hope that the Kingdom may come soon in fullness. But as an evidence of that hope we should also reaffirm our willingness to be the community of disciples of Christ which tries to demonstrate in the context of development or underdevelopment, affluence or poverty, democracy or dictatorship, that there is a different way for men to live together dealing with passions, power, relations, inequality, and privilege; that we are not only able to proclaim that ‘the end is at hand’ but also to encourage one another in the search to make this world a bit less unjust and cruel, as an evidence of our expectation of a new creation.

I join Escobar in asking: Do we stand with the rich or with the poor? Do we usually stand with oppressors or with the oppressed? Where do we stand when we preach the gospel?