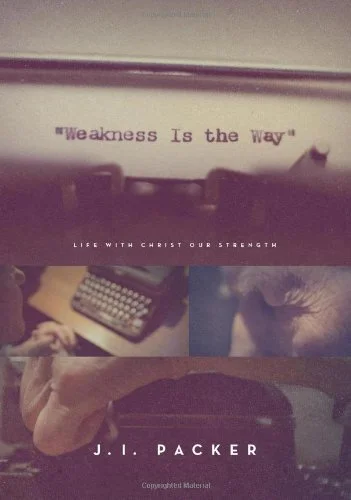

Weakness is the Way

When J.I. Packer was a young boy, he was hit by a bread truck. The injuries were serious—he had damage to the frontal lobe of his brain and a hole in his skull—landing him in the hospital for three weeks and out of school for six months. When he returned to the classroom, he did so wearing a metal plate to cover the dent in his head. Never again could he play with his peers outside.

Packer is now 87 years old and is likely nearing the final years of his life. But a lot has happened in these 80 intervening years since his childhood injury. While the accident imposed all kinds of limitations on him, in the end, it was not enough to sideline him. On the contrary, the respected Anglican teacher and scholar has written dozens of books, including the classic Knowing God, and has become one of the most prominent evangelicals (in the original, theological sense of the term) in North America and in his native England.

Most recently he’s the author of Weakness Is the Way: Life with Christ Our Strength, a slim book that is nonetheless seasoned with a lifetime of wisdom—and yes, tempered by weakness.

Packer’s meditations on the significance of weakness in the life of Paul are especially illuminating. Before he met Jesus on the Damascus Road, of course, Paul prided himself on having it all together. He was not, as Packer says, “weakness-conscious” in his early years. But all of that would change, compounded by shipwrecks and arrests and beatings and, of course, that nasty, mysterious thorn in his flesh (whatever that may signify).

“And we should recognize,” Packer writes, “that the fierce and somewhat disabling pain with which Christ in due course required [Paul] to live, and which he clearly accepted as a weakness that would be with him to his dying day, had in view less the enriching of his ministry than the furthering of his sanctification.”

The notion that God might intend us to live with weakness, pain, and suffering for extended periods of time—even to our dying day—isn’t going to sit well with most of us. It doesn’t sit well with me. But I’m not sure this makes the notion any less true. Packer concludes:

When the world tells us, as it does, that everyone has a right to a life that is easy, comfortable, and relatively pain-free, a life that enables us to discover, display, and deploy all the strengths that are latent within us, the world twists the truth right out of shape. That was not the quality of life to which Christ’s calling led him, nor was it Paul’s calling, nor is it what we are called to in the twenty-first century. For all Christians, the likelihood is rather that as our discipleship continues, God will make us increasingly weakness-conscious and pain-aware, so that we may learn with Paul that when we are conscious of being weak, then— and only then— may we become truly strong in the Lord.

Packer writes plainly about weakness because he has no choice; it’s the soil in which his life has been planted, and the roots are going deeper as the years go by. Reading these reflections from a seasoned, weathered saint has been good for me.

As I ponder all of this, I’m reminded of the words of another man who was acquainted with sorrow, the late singer-songwriter Rich Mullins:

We are frail

We are fearfully and wonderfully made

Forged in the fires of human passion

Choking on the fumes of selfish rage

And with these our hells and our heavens

So few inches apart

We must be awfully small

And not as strong as we think we are

This is the truth, no matter how we feel in our most invincible, invigorated moments: We are not as strong as we think we are.

But this is also true: Christ is our strength, and he is more than enough.

Amen.