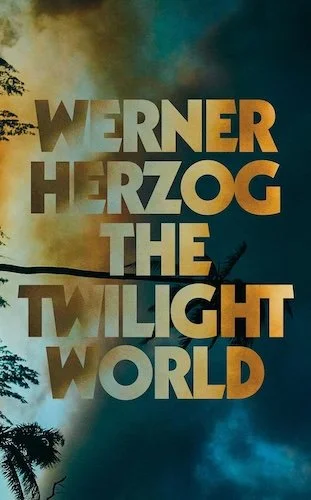

The Twilight World

As a filmmaker, Werner Herzog has long been drawn to stories about the extremities of human experience. And in The Twilight World, a semi-biographical novel, the same holds true.

This is the bizarre but (mostly) true story of Onoda, a lieutenant in the Japanese army who in 1944 is sent to the Philippine island of Lubang with orders to protect it against enemy incursion at all costs—the enemy in this case being, of course, the United States and its allies. Onoda is instructed to defend the island initially by bombing the air strip and destroying the dock. He fails at both tasks, but otherwise follows orders scrupulously. For a very long time.

Left to survive in the jungle with a motley crew of soldiers with varying degrees of professionalism and survival instinct, Onoda and his band pass their days mostly hiding but occasionally stealing from or shooting civilians. One by one, however—whether through defection or death—Onoda’s companions leave him. And then he is left all alone.

Still he persists in his mission. When leaflets are dropped declaring the end of the war, he tells himself they are enemy ploys. His faith in Japan’s eventual victory is unwavering. He will know the war is over when his fellow troops return en masse and his commander relieves him of duty.

When military planes fly overhead in new patterns—coinciding, the omniscient reader knows, with the start of the Korean War—Onoda takes it as confirmation that the war is ongoing, with the front having simply shifted to new shores. So he waits, and waits some more.

Japan will win the war. And Onoda doesn’t care how long it takes.