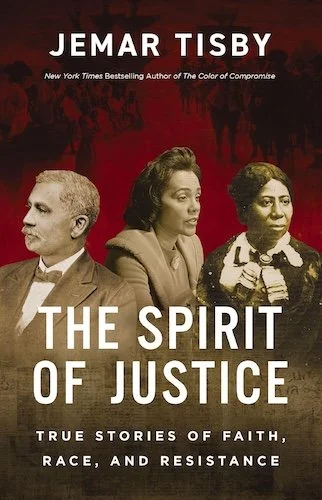

The Spirit of Justice

The historian Jemar Tisby’s essential and challenging 2019 book The Color of Compromise is the story of “the American church’s complicity in racism” from pre-revolutionary times to the present day. Now, in The Spirit of Justice: True Stories of Faith, Race, and Resistance (Zondervan) he tells an equally important story: how women and men throughout United States history have courageously and sacrificially sought racial justice as a faithful embodiment of their Christians convictions.

“In the United States, the Black church stands as the clearest demonstration that Christianity is not the white man’s religion,” Tisby writes. “Highlighting Black Christians in a historical exploration of the struggle against racism makes sense because the Black Christian tradition arose as an explicit refutation of racism and white supremacy.”

This book really does cover quite a lot of ground. But allow me to focus on just one piece of the story for a moment. In an early chapter we learn about the painful origins of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church. During a worship gathering of a Methodist congregation in Philadelphia in 1787, “white church officials attempted to pull Black worshipers off their knees and into a segregated section” of the building.

Stop there. Visualize that. Think about the hands, the knees, the feet. Think about the hearts and minds. The souls. Dwell there in the discomfort. Sit with it for a moment longer than you’d like.

This incident, one of so many like it, is all the more jarring when we consider that John Wesley, one of Methodism’s founders, had been outspoken in his denouncement of slavery. (The Methodists, in this regard, were some of the good guys!) Wesley taught that Christians demonstrate lives of holiness first of all “by avoiding evil of every kind,” naming slavery as one of the “generally practiced” evils of the day. And that teaching wasn’t peripheral; during the formation of the Methodist denomination in the United States in 1784—just three years prior to the racist incident in Philadelphia—ministers officially condemned slavery, rightly regarding that flagship form of institutionalized racism as an affront to the teaching of Jesus to “Love your neighbor as yourself.”

The church leaders in Philadelphia knew what was right. And they knew, at some level, that racism was wrong. They knew—as you and I do—that pastors shouldn’t physically restrain people from praying at church just because they’re Black.

But the temptation to acquiesce to unholy pressures was (and is) strong. “Few ministers were willing to oppose the wealthiest members of their congregations over the issue of slave trading or slaveholding,” Tisby writes. “The Methodist documents themselves often came with the caveat that the state laws should be respected.”

Richard Allen, Absalom Jones, and the other Black Methodists who eventually founded the AME wanted nothing more than to worship and serve with integrity. But in the church where they had been nurtured, that was grievously no longer possible. And so they left to build a church where their bodies would be safe, to cultivate a tradition, with God’s help, where goodness and courage and faithfulness could grow.

Black Christians have always led the movements to end slavery and to establish racial justice in this country, and it is these stories that The Spirit of Justice primarily seeks to tell. Christians like me would do well to remember, learn from, and honor the collective witness of the Black church in doing justice, loving kindness, and walking humbly with God. Yet Tisby also highlights the ways white Christians, including Quaker abolitionists, have contributed to the work of justice right where they are as well. And he reminds us of something else that’s critical, “that the labor of convincing other white people of the need for racial justice is a task white people must undertake for themselves.”