The Poisonwood Bible

In The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver, we’re introduced to Nathan Price, a fierce Baptist missionary with an independent streak who took his family to the Congo in the late 1950s. Narrated by his wife and four daughters, it’s a spellbinding story. It’s also brutal, particularly in its indictment of Price for his selfishness, legalism, heavy-handedness, arrogance, and callous disregard for the wellbeing of his family and of those he has purportedly been sent to serve. He’s not only an ugly American, he’s also an ugly Christian.

Kingsolver’s own childhood included a brief stint in the Congo as the daughter of an American physician, and this experience undoubtedly shaped the way she sees the world. Interestingly, though, in the Author’s Note she writes:

I thank Virginia and Wendell Kingsolver, especially, for being different in every way from the parents I created for the narrators of this tale. I was the fortunate child of medical and public-health workers, whose compassion and curiosity led them to the Congo. They brought me to a place of wonders, taught me to pay attention, and set me early on a path of exploring the great, shifting terrain between righteousness and what’s right.

As a son of missionaries, and one with a particular interest in matters of faith, ethics, and justice, I’d wanted to read The Poisonwood Bible for a long time, and I’m glad I finally had the chance. It really is a great novel. And while the damning portrayal of Nathan Price is admittedly a caricature, an honest look at the history of Christian mission reveals that self-identified followers of Christ have at times been involved in some pretty awful stuff.

Which raises an important question: Do missionaries destroy cultures?

Veteran missionary Don Richardson, best known for his books Peace Child and Eternity in Their Hearts, addresses this question in an article in Perspectives on the World Christian Movement: A Reader (article available as a PDF here).

“There have indeed been occasions when missionaries were responsible for needless destruction of culture,” Richardson writes. “Whether through misinterpreting the Great Commission, pride, culture shock, or simple inability to comprehend the values of others, we have needlessly opposed customs we did not understand. Some, had we understood them, might have served as communication keys for the gospel!”

But Richardson goes on to argue – convincingly, I think – that missionaries who destroy cultures are the exception; most are far more often hard at work preserving languages and cultures, and serving communities in practical, tangible ways through education, public health, or other community development initiatives.

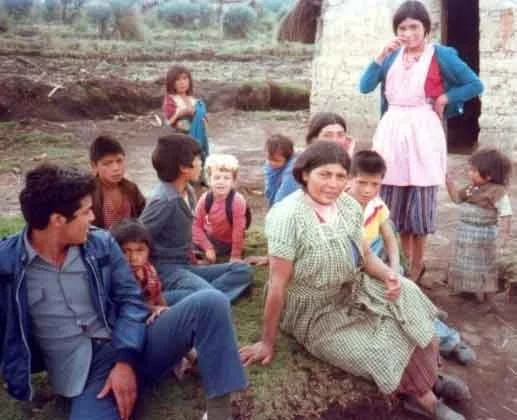

My own parents served in the highlands of western Guatemala for many years as missionary linguists, and far from seeking to destroy the local culture, they honored and respected it, while teaching us to do likewise. Eventually we did.

For better or worse, remote communities no longer have the option of remaining “undisturbed,” even if that’s what they’d prefer. It’s well known that in the Amazon region, for instance, loggers continue to encroach on indigenous land all the time. And as self-described atheist Matthew Parris famously wrote a few years ago regarding another continent, “Removing Christian evangelism from the African equation may leave the continent at the mercy of a malign fusion of Nike, the witch doctor, the mobile phone and the machete.”

It’s true that people who more or less resemble Nathan Price exist, and some of them call themselves missionaries. But when missionaries are at their best, Richardson writes, they “are advocates not only of spiritual truth, but also of physical survival.” He describes how his own service in Indonesia included persuading his neighbors to give up the practice of cannibalism, knowing that if they didn’t do so willingly, the Indonesian government would have forced the point through truly aggressive means. In that way, he had a hand in changing the culture, which in turn kept it from being destroyed:

Do missionaries destroy cultures? It’s true that we destroy certain things in cultures, just as doctors sometimes must destroy certain things in a human body if a patient is to live. But as we grow in experience and God-given wisdom, we must not – and will not – destroy cultures themselves.

Once again, you can read the entire article here, which I’d recommend you do – right after you read The Poisonwood Bible for yourself.