The Locust Effect, Reconsidered

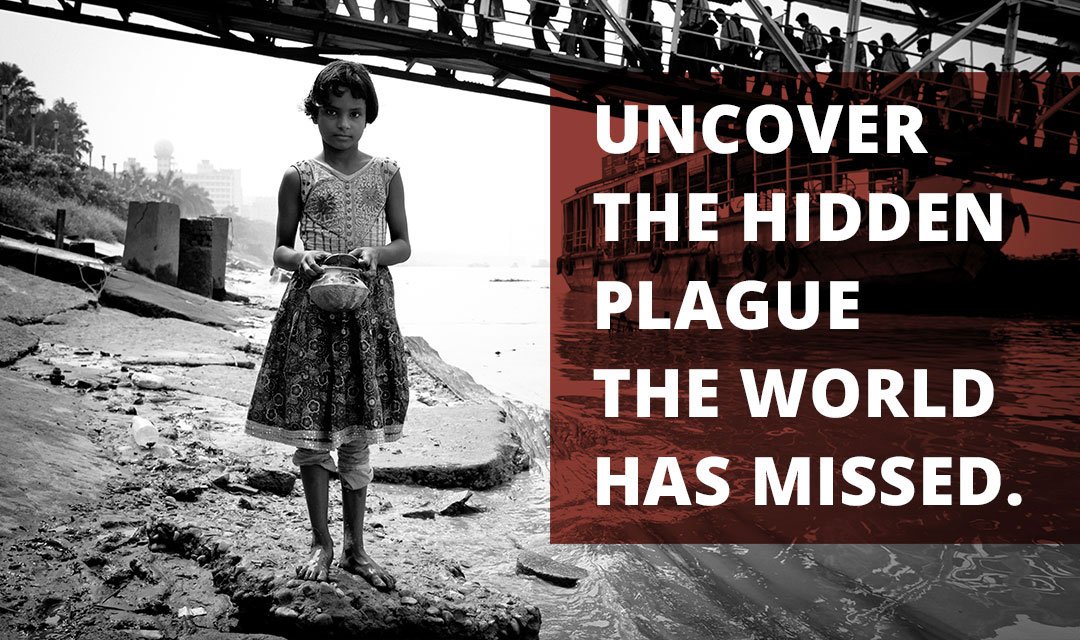

One of the most important books of recent years, in my estimation, is The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence by Gary Haugen and Victor Boutros.

In my review I wrote, “With great moral urgency, The Locust Effect issues a clarion call to courageous action on behalf of the vulnerable poor. The sobering news is that the plague of hidden, everyday violence is real. The good news is that it is not inevitable.”

Haugen has been a hero of mine for years because of his work with International Justice Mission, but I’ll admit this was my first introduction to Victor Boutros, a federal prosecutor with the U.S. Justice Department whose work, like that of IJM, focuses on human trafficking as well.

A couple of weeks ago, Boutros delivered a lecture titled “Public Justice: A Matter of Life and Death for the World’s Poor” as part of the annual Kuyper Lecture series, sponsored by the Center for Public Justice. I hope the video of Boutros’ lecture will be made available at some point, but for now we have the transcript. This excerpt might be said to represent the core of Boutros’ argument:

History is full of horrifying stories of poor farm families forced to watch helplessly as a plague of locusts suddenly descends to devour their crops – and, in a matter of hours, destroys years of effort trying to plow and plant their way out of poverty. Likewise, it seems that we are approaching a pivotal moment in history where agreement is emerging that if we do not decisively address the plague of everyday violence that swarms over the common poor in the developing world, the poorest will not be able to thrive and achieve their dreams – ever.

In his response to the lecture, CPJ founder Jim Skillen (whose new book on politics I’ll be reviewing soon) didn’t exactly disagree with the core argument. But he did challenge Boutros to reach back even further than the plague of violence:

Victor is correct to point to the importance of historical development over the past 100 and more years, developments that have led to many advances in law enforcement in cities such as New York. But better law enforcement and criminal justice institutions in those cities did not arise independently, apart from wider political and governmental reforms, including establishment of the rule of law to hold government and citizens accountable, making room for some degree of freedom for the press and other associations of citizens, and establishing court systems that allow ordinary citizens to present suits against government corruption and abuse. My point is simply that if there can be no end to poverty without the end of violence, there can be no end to violence without an end to unjust political institutions across the board. Law enforcement and court systems are just one part of government in a political community.

Another respondent was Rob Joustra, who teaches courses on political science and international studies at Redeemer University College, and is associated with both the Institute for Global Engagement and the Center for Public Justice. (His review of The Locust Effect, in which he emphasizes the book’s apparent Kuyperian influences, was published in Books and Culture earlier this year.) In his short, entertaining response to the lecture, Joustra brings St. Augustine into the mix with this insightful comment:

It’s not merely the coercive power of the state that restrains anarchy and “the state of nature”; it is also our formed desire in communities of virtue. I don’t live in special fear of my neighbor robbing or raping me not only because of the working apparatus of peace, order, and good government that we Canadians cherish, but also because I know my neighbor has had his desires formed in such a way that he actually doesn’t want to do that. This is the insight that people like David Naugle or Jamie Smith give us in their popular accounts of Augustine: the key to public justice isn’t for us to “follow our hearts” and the state will restrain us if we get out of hand. The key to public justice is for us to “discipline our hearts,” to be attentive to the formation of our desires. Or, as the Psalmist puts it more pointedly, “How can a young man keep his way pure? By meditating on God’s law, day and night.”

As I said at the top, I consider The Locust Effect almost unparalleled among recent books in terms of real importance. And Skillen and Joustra both hint at its gravitas, which is why these somewhat critical responses are so important and healthy for a much-needed debate like this.

Echoing the line of thought in the book, Boutros in his lecture points to public justice—and especially the prevention and prosecution of violent crime through criminal justice—as a woefully overlooked aspect of development. Skillen and Joustra, meanwhile, show how the emphasis on clamping down on violent crime as a means of alleviating poverty could be misconstrued if divorced from broader public justice concerns and the (re)formation of desire, respectively.

All of this dovetails nicely, I think, with another point I made in my review of The Locust Effect as a way of commending the authors: “Making a forceful and convincing case for one thing does not require pretending that nothing else matters; others who write about poverty and development should take note.”

Given all the pettiness and meanness alike that sour our world, we can be grateful that debates like these are happening—and that in the end lives, communities, cities, and nations are being shaped for the better.

If you haven’t read The Locust Effect yet, I really encourage you to do so. Then spend some time considering the thoughtful responses from Skillen, Joustra, and others.