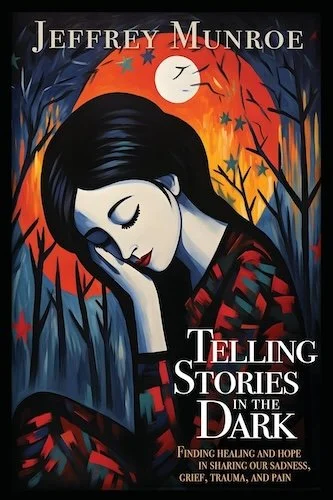

Telling Stories in the Dark

Years ago, the late Frederick Buechner spoke memorably about the “stewardship of pain.” Drawing upon his own traumatic experiences as a child, Buechner wanted to offer the world something that might just contribute to the healing of others, even while attending to his own wounds.

Buechner would have certainly been aware of the risks in speaking from and about one’s pain. He would have known that the time to speak isn’t necessarily right away. He would have sensed that his words, if not carefully chosen, might do more harm than good. He would have known that in his vulnerability, there was a good chance he wouldn’t always feel felt by his hearers and readers. It was possible—very possible—that further pain and isolation might lie around the bend.

But at an even deeper level, Buechner must have sensed that there was wisdom in articulation, risks and all. And in his memoirs, the generosity and restraint in his writing—and no, those two things are not at odds—have been gifts to so many of us.

Buechner’s wisdom lives on, and finds beautiful new expressions, in Jeffrey Munroe’s book Telling Stories in the Dark: Finding Healing and Hope in Sharing Our Sadness, Grief, Trauma, and Pain (Reformed Journal Books). Munroe, for his part, has had his fair share of pain to steward, and we do learn some of his story here. But this isn’t a navel-gazing book. Instead, in a truly unique approach, Munroe invites us into his life as well as the stories of people he knows who have walked a variety of difficult paths. In each chapter, he then brings in a “guide,” you might say—a theologian or pastor, a psychologist or painter—to reflect on the story just recounted with wisdom and grace.

The stories here are deeply moving. They break our hearts and begin to mend them, if only just a little bit. In a chapter titled “The Long Goodbye,” for example, Munroe writes lovingly and honestly about his mother and the dementia that took so much from her (and those who loved her) during the final years of her life.

In response to that story, the theologian Suzanne McDonald writes, “It’s vitally important to realize there is more to personhood than memory. If all we focus on is memory, we are going to struggle to see personhood in someone in the depths of dementia.” McDonald goes on to remind us that even when shorter-term memory goes, a person with dementia will likely retain access to other, equally valid forms of memory. A person who forgets what she had for breakfast this morning may well come alive when she hears her favorite song. She may still be able to ride a bike. If she’s part of a liturgical church tradition, her body may remember when to sit, stand, or kneel. Particular smells may remind her of a long-gone parent or a dear old friend.

“As we think of someone’s personhood and how to walk well with someone with dementia,” McDonald writes, “we should ask how we can tap into these other types of memory. Can we become the guardians of someone’s personhood when they can no longer hold it for themselves?”

Guardians of personhood—what a wonderful way to conceive not just of being a caretaker for a person with dementia, but of the joyful responsibility and grave privilege of walking alongside people in pain or disorientation of varying kinds. To say through our faithful presence as much as through anything else, Your dignity is not past tense. Your personhood has no expiration date. Your wellbeing is worth defending. No matter what. However long it takes.