Return of the Prodigal Son

In Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming (Image Books), Henri Nouwen reflects on the well-known parable through the lens of Rembrandt’s classic depiction of it. Over the course of the book, Nouwen sees himself in the waywardness of the younger brother, he sees himself in the self-righteousness of the elder brother, and ultimately, he sees that’s he’s called to become like the compassionate, welcoming Father in his grief, his forgiveness and his generosity.

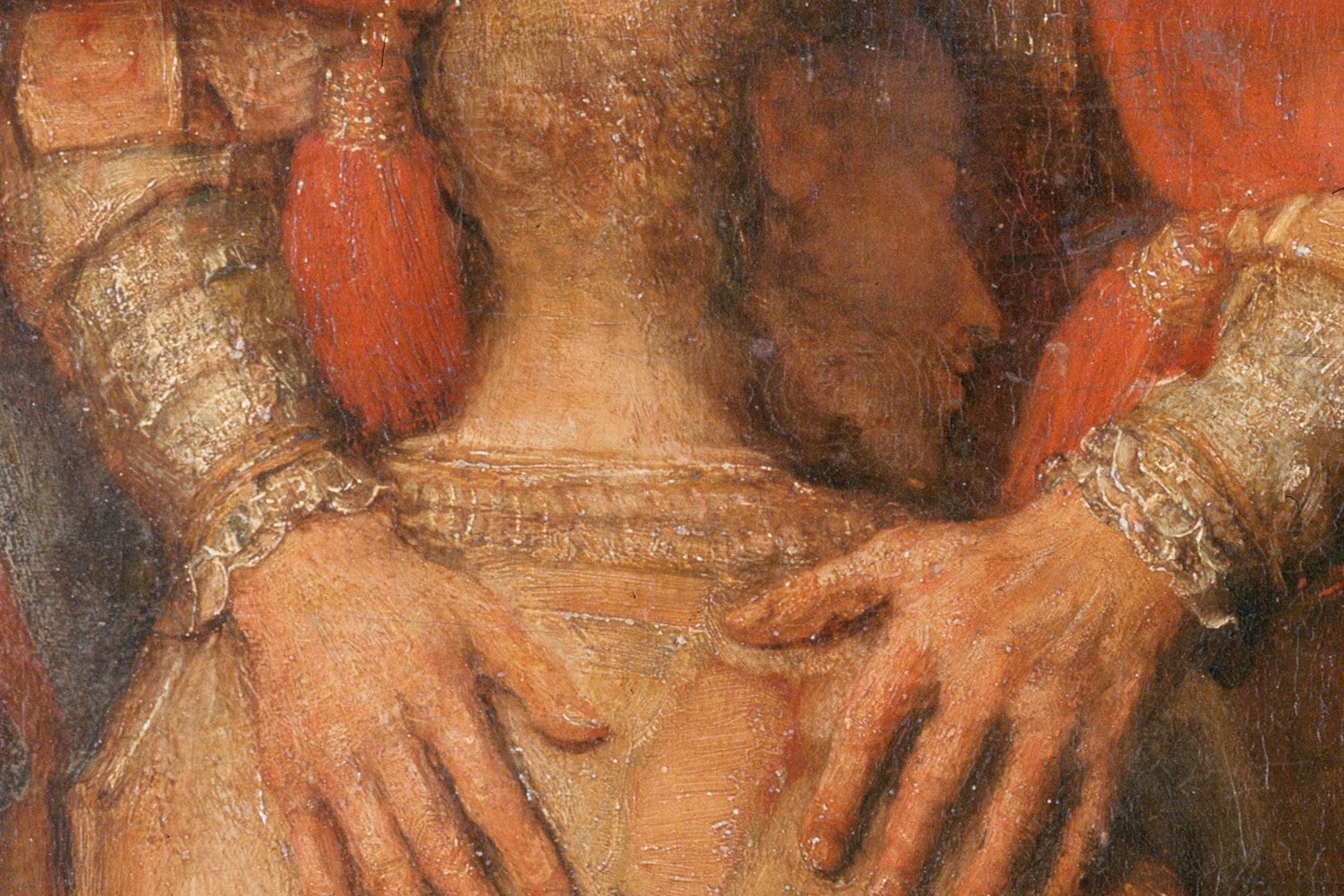

Near the end of the book, having reflected on the many ways in which we are all the younger brother who squanders what’s entrusted to us, and how we’re all the elder brother standing aloof, thinking ourselves better than our brother, he turns to the wonderful truth that even so we’re invited to the Father’s embrace and celebration. The younger brother enters the party with repentance and joy, but in the parable and in Rembrandt’s painting the elder brother’s story is left unresolved. We don’t know whether he’ll accept the invitation or whether he’ll remain stiff, standing alone, in the shadows.

Our world is marked by much that is not right, much that is broken. We see some of that brokenness in the inner and outer lives of the brothers, in their relationship to each other and in their relationship with the Father. But the Christian hope is that one day all things will be made new, and that will be cause for some real joyful celebration. In the meantime, however, there are small joys. “I don’t have to wait until all is well,” Nouwen writes, “but I can celebrate every little hint of the Kingdom that is at hand.” We live simultaneously in the already and the not yet:

When Jesus speaks about the world, he is very realistic. He speaks about wars and revolutions, earthquakes, plagues and famines, persecution and imprisonment, betrayal, hatred and assassinations. There is no suggestion at all that these signs of the world’s darkness will ever be absent. But still, God’s joy can be ours in the midst of it all. It is the joy of belonging to the household of God whose love is stronger than death and who empowers us to be in the world while already belonging to the kingdom of joy.

This is the secret of the joy of the saints. From St. Anthony of the desert, to St. Francis of Assisi, to Frere Roger Shultz of Taize, to Mother Teresa of Calcutta, joy has been the mark of the people of God. That joy can be seen on the faces of the many simple, poor, and often suffering people who live today among great economic and social upheaval, but who can already hear the music and the dance in the Father’s house. I, myself, see this joy every day in the faces of the mentally handicapped people of my community. All these holy men and women, whether they lived long ago or belong to our own time, can recognize the many small returns that take place every day and rejoice with the Father. They have somehow pierced the meaning of true joy (pp. 116-7).

Our hopeful expectation isn’t that someday we’ll be whisked away from this fallen world; rather, it’s that someday Christ will make all things new. It’s a down-to-earth hope, but it’s also cosmic and glorious. It’s truly good news. In the meantime, these already-but-not-yet words of Jesus ring true and make joy a real possibility even now: “In this world you will have trouble. But take heart! I have overcome the world.”