René Padilla: Gospel “Teeth” (The Lausanne Series, Part 1)

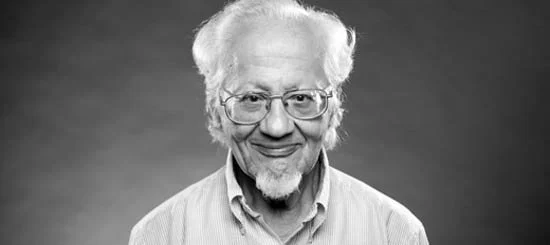

Last week I introduced this new series on the Lausanne Movement and its contributions to a better understanding of the intersections of faith, development, justice and peace. As I mentioned in that post, I’m going to begin with a presentation from René Padilla titled “Evangelism and the World.” Padilla is originally from Ecuador, and along with Samuel Escobar (who we’ll turn to next week) he was a pioneer of what became known in Latin America as “integral mission.” He was also a leader of the Latin American Theological Fellowship and has written a number of books including Mission Between the Times: Essays on the Kingdom.

Taking a look at the spectrum of Christian belief and practice at the time, Padilla saw two “extreme positions.” On the one hand, adherents of the social gospel in North America, and proponents of liberation theology throughout Latin America, understood salvation to be limited to the physical, political and social realm. Meanwhile, fundamentalists and evangelicals were reducing salvation to the future destiny of the soul. Both views of the gospel are incomplete, Padilla argued, saying that Christians must embrace “the whole Gospel for the whole man for the whole world.” He continued:

On the one hand, the Gospel cannot be reduced to social, economic and political categories, nor the church to an agency for human improvement… On the other hand, there is no biblical warrant to view the church as an other-worldly community dedicated to the salvation of souls, or to limit its mission to the preaching of man’s reconciliation to God through Jesus Christ.

In this presentation in 1974, I’m sure Padilla ruffled some feathers, though he believed that for the most part he had a sympathetic audience (he was, after all, speaking to a room full of people committed to the gospel and its global implications). Like Dietrich Bonhoeffer a generation or so before him, Padilla issued a devastating critique of superficial evangelism, what Bonhoeffer called “cheap grace.” Padilla argued that evangelism is about more than just getting people to believe a certain set of doctrines to ensure a future reward: “The aim of evangelization is… to lead man, not merely to a subjective experience of the future salvation of his soul, but to a radical reorientation of his life.”

This radical reorientation of one’s life, he goes on to say, has unavoidable ethical and social implications. Padilla doesn’t deny the relationship between the gospel and personal holiness (and neither do I!), but knowing his audience, he was zeroing in on a huge blind spot. Evangelicals had all too often concentrated on “microethics” while tending to shy away from anything having to do with “macroethics.” People being shaped by the gospel ought to be concerned about both, he argued.

What’s more, he critiqued the pervasive problems of worldliness in the church, adapting the gospel to the “spirit of the times.” While evangelicals were quick to decry secularization, he said, they often failed to recognize the ways in which their understanding and practice of Christianity was shaped more by the prevailing culture than by the gospel. This isn’t a problem unique to North American Christians by any means, but given American Christianity’s influence around the world, confusing Jesus’s offer of abundant life with the American Dream presents a serious problem for Christians everywhere.

Recognizing our propensity to confuse the gospel with our culture’s understanding of “the good life” should lead us to a process of prayerful discernment, seeking to contextualize without becoming syncretistic, to use a couple of big missiological terms. When we fail to contextualize well, we either withdraw from the world we’re called to love, or we become no different from the world; both represent unfaithfulness to our Lord. In ethical and social terms,

When the church lets itself be squeezed into the mold of the world, it loses the capacity to see and, even more, to denounce, the social evils in its own situation… A Gospel that leaves untouched our life in the world — in relationship to the world of men as well as in relationship to the world of creation — is not the Christian Gospel, but culture Christianity, adjusted to the mood of the day. This kind of Gospel has no teeth.

By marching along in the world’s parade, favoring quantity to quality, and embracing technological efficiency in our churches and ministries without question, Padilla argued, we reduced the gospel to a “cheap product” and “turned the strategy for the evangelization of the world into a problem of technology.” Technology and efficiency have their place, he said, but “it is to this absolutization of efficiency, at the expense of the integrity of the Gospel, that I object.”

For those of us who would say we take the Bible seriously, we’d do well to examine our understanding of the gospel to see whether, in light of Scripture, these critiques have merit. What cultural values or norms have we absolutized at the expense of the integrity of the gospel? How have we adjusted the gospel to the mood of the day?

For those of us who are part of the church in the U.S., who can’t simply shake off our culture, we’d do well to ask how we can overcome the temptation to settle for cultural Christianity. At the same time, for those who are part of the church in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and elsewhere, the challenge is to be proactive, to avoid creating your own culturally-modified, toothless Christianity.

The gospel is to be incarnated in culture wherever we are, affirming what is good, resisting what is evil, and discerning, through the guidance of the Holy Spirit, where that distinction lies. I’m grateful to René Padilla for helping us begin that process of discernment.

I shared this video last September, but here René Padilla and Samuel Escobar, as Latin American leaders, reflect on the Lausanne Movement’s accomplishments and shortcomings. Next week I’ll take a look at Escobar’s presentation at Lausanne in 1974.