Reading Encyclicals

In the Winter 2015 issue of Comment magazine, there is a wonderful essay by Brian Dijkema titled “How to Read an Encyclical (and Why).” Described as “a Protestant’s grateful guide” to the papal documents that have guided Roman Catholic thinking and practice for many years, I found it truly revelatory.

As 2016 has gotten weirder and weirder, I keep thinking about that essay and about the under-appreciated gift papal encyclicals really are for times like these. “The encyclicals are a repository of wisdom we’ve forgotten,” Dijkema writes, “which also turns out to be just what we need in the modern age.”

For Protestants, of course, there will be the usual, well, protestations. If you’re one of us, you probably have several on the tip of your tongue. So, why bother with encyclicals? Here’s Dijkema:

If you’re not a Roman Catholic, or not even a believer, why read them at all? They are worth reading for Protestants because – in a manner that contemporary Protestant writing still only dreams of attaining – they take the time to pore both through the Scriptures and through the breadth of the Christian tradition to testify to the person of Christ in life right here, right now. And readers who aren’t Christians often find themselves intrigued, curious, and maybe just a bit attracted to a community that can talk with such depth and clarity about the anxieties of our age, and that presents a coherent and beautiful vision for the good life in an age that too often settles for a mere collection of shards.

Even though for a decade or more I’ve been consistently reading, writing, and talking with friends about books having to do with questions of Christian faith and our lives in the world – you know, books about justice, work, citizenship, etc. – until last spring I never thought to pick up an encyclical, nor can I recall a single instance of someone I know suggesting I read one.

That’s kind of strange, isn’t it? Especially considering the ground encyclicals cover. Dijkema summarizes: “Papal encyclicals are diagnoses of particular historical ailments – the encyclicals speak about work (Laborem Exercens), the environment (Laudato Si’), religious freedom (Dignitatis Humanae), birth control (Humanae Vitae), the state and civil society (Centesimus Annus), development (Popularum Progressio, Caritas in Veritate) – and as such, they offer different prescriptions.”

Granted, during this election cycle our tidy right-left paradigms have undergone a major (indeed, huuuuge) shakeup, in which a candidate with approximately zero conservative credentials has become the presumptive Republican nominee, and in which a candidate who appears to remain unaffiliated with the Democratic party nonetheless continues to seek that party’s nomination.

That said, the categories employed by the encyclicals continue to confound us – in a good way. Dijkema writes:

If progressives are obsessed with a manic drive to move forward and are willing to burn in order to facilitate their social experiments, and if (unredeemed) conservatives are those who (with apologies to Buckley) merely stand athwart history yelling ‘Stop!’ but have nothing else to say, the papal encyclicals say, ‘Come, let us reason together’ and move forward according to a robust, whole, and full conception of what it means to be human.

The truth is, there are problematic areas in life where progress is needed, just as there are good things in life worth conserving. To admit as much, and to be willing to follow that belief to its logical conclusion, may make for uncomfortable conversations at Thanksgiving dinner. But such a conviction doesn’t make for a bad Christian.

As Dijkema puts it, “The insistence on maintaining an integral vision of human life is a scandal to an age that forgets (or ignores) that there might be such a thing as a whole with a purpose.” I think a lot of us are hungry for such a vision. I know I am.

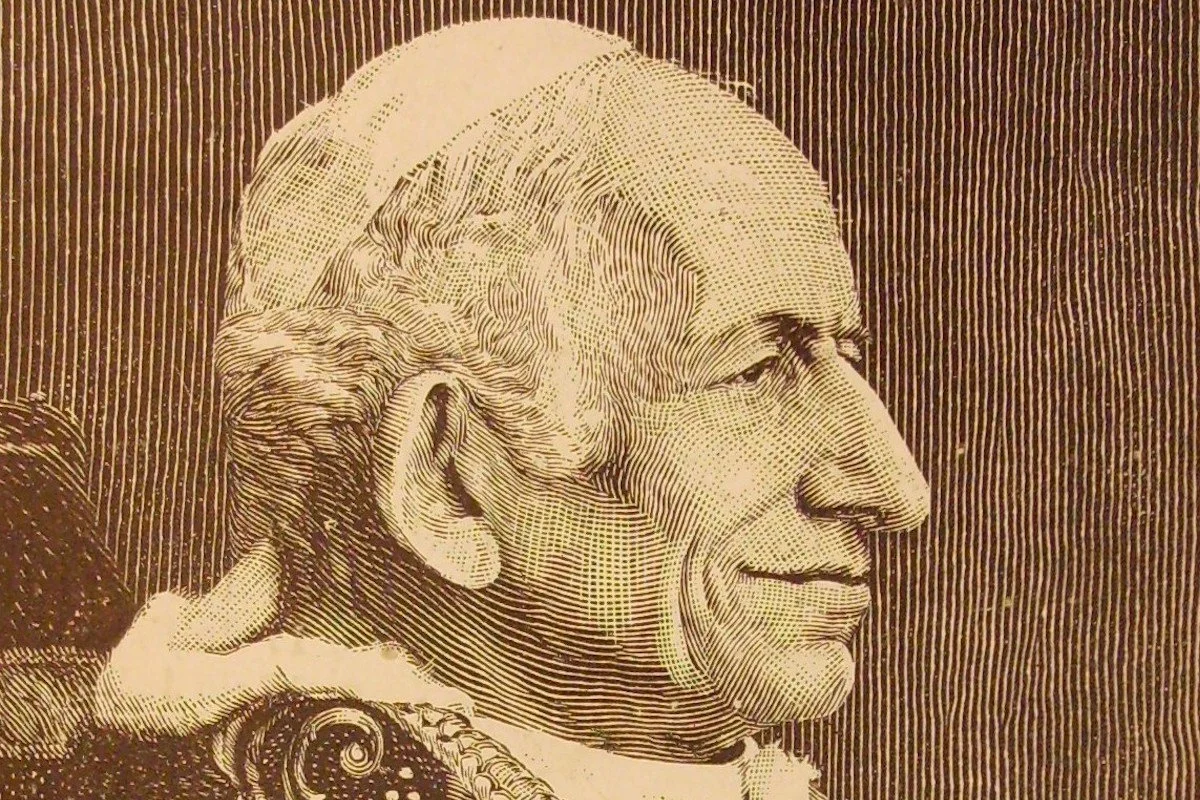

Last spring I finally dipped my toes in the encyclical waters by reading Caritas in Veritate (“Charity in Truth”), the third and final encyclical from Pope Benedict XVI. Published in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2007-08, Benedict used the letter to advocate for “integral human development,” arguing that “charity is at the heart of the Church’s social doctrine” and that “every economic decision has a moral consequence.” It’s a wide-ranging document, as encyclicals tend to be, and will confound (again, in a good way!) most everyone at one point or another. It also strikes me as measured and wise.

More recently I picked up Laudato Si, the second and most recent encyclical from Pope Francis, having to do with ecology and environmental stewardship. While acknowledging and affirming the “cultural mandate” of Genesis 1:28 (which is sometimes used, wrongly, to condone environmental destruction), Francis appeals to his readers within the church and people of goodwill outside it to look carefully at the “common home” we have inherited and to consider the ways we’ve shortsightedly reduced aspects of it to ruin.

Ultimately, like other encyclicals Laudato Si’ is written to help us see God in all aspects of life in the world – and to prompt us to respond in gratitude:

The universe unfolds in God, who fills it completely. Hence, there is a mystical meaning to be found in a leaf, in a mountain trail, in a dewdrop, in a poor person’s face. The ideal is not only to pass from the exterior to the interior to discover the action of God in the soul, but also to discover God in all things. Saint Bonaventure teaches us that ‘contemplation deepens the more we feel the working of God’s grace within our hearts, and the better we learn to encounter God in creatures outside ourselves.’

It seems to me that especially now, given the fragmentation, anger, and disillusionment that characterize our times, the “integral vision of human life” presented to us in the encyclicals is a rare gift. That, in a nutshell, is what this long, meandering post has been trying to convey.

I’m not going to say you should take Rerum novarum or Evangelium vitae with you to the beach this summer, but for what it’s worth, I might do just that myself.