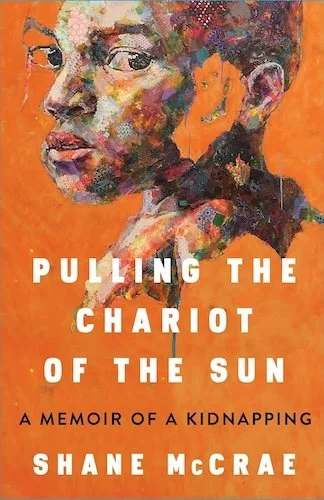

Pulling the Chariot of the Sun

Shane McCrae’s memoir Pulling the Chariot of the Sun (Scribner) is a difficult book to read and a tricky book to review.

It’s difficult to read because it’s the true story of a kidnapping—namely, the kidnapping of the author, by his white grandparents, when he was three years old. They kidnapped him because his father was Black and because they were the kinds of racists who say the quiet parts out loud—and act accordingly. His grandparents wanted to “save” him, in some twisted sense, from his blackness. Even if it meant lying to him about his father. Even if it meant beating him into submission until he started calling them “Mom” and “Dad.” Even if it meant stealing his childhood.

So yes, this book is difficult to read for all these reasons. But it’s also a challenging book to review because of the author’s audacious literary choices.

McCrae is an accomplished poet who teaches in an MFA program at Columbia University. I’ve read enough of his work to know he uses words with greater intentionality than most of us. He deserves our trust in that regard. But there are some long, very long, sentences in this book. What’s more, many of these sentences contain repetitions and contradictions, as if he’s editing himself (second-guessing himself?) in real time.

These bold choices do, in many cases, serve the book well; McCrae knows what he’s doing. Indeed, a boy who is kidnapped as a toddler and raised by abusive, deceptive grandparents—such a child is eventually going to grow into a man who carries complicated and confusing burdens wherever he goes. And one of the ways childhood trauma quite often reveals itself is in a fracturing of the memory. In a memoir about such a childhood, then, it would be one thing to explain this fracturing; it’s another thing entirely to demonstrate it.

A taste of McCrae’s profundity as well his capacity to bewilder:

“An occasion of terror is fundamentally unlike other occasions, and what makes an occasion of terror remarkable enough to be remembered also makes it seem as if it doesn’t belong in one’s memory; a remembered occasion of terror is a transplanted organ the body constantly tries to reject, or does reject, sometimes the body does reject it, and a hole where the memory of the original occasion of terror was or might have been is left, a space seems to be hollowed out for the memory even if the memory never occupies a space in the mind, and the hole where the memory was or might have been becomes itself an occasion of terror, but slower, but slower than the original occasion, and longer than the original occasion, boundaryless, unending, but one can turn one’s attention from it. I only notice it when I look at it, terror as the background noise of undifferentiated voices in a large crowd, the thousands of conversations in a stadium, terror as the inability to isolate a voice and comprehend it, that one can be in a stadium in which one’s memories speak, but neither to one nor to each other, and incomprehensibly, so that the noise of one’s memories is in some ways silence, but a silence of varying shades” (pp. 114-115).

Sentences like those can be a lot to handle—especially when they appear on page after page after page. But by book’s end, patient readers will be rewarded for their trust.