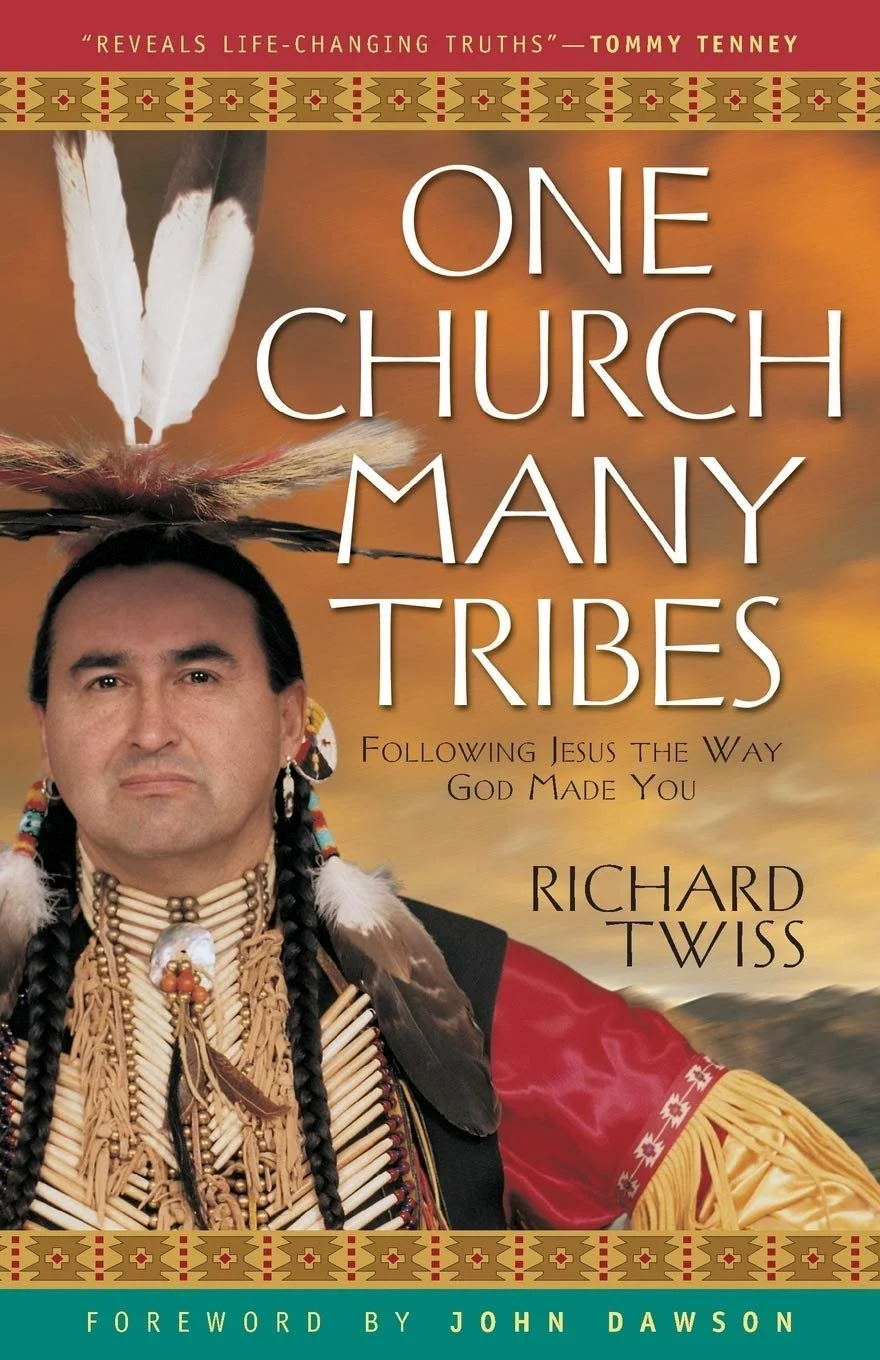

One Church, Many Tribes

A couple of weeks ago I read One Church, Many Tribes (Regal) by Richard Twiss, a member of the Rosebud Lakota/Sioux tribe and the head of Wiconi International. Through Wiconi, Twiss serves Native groups through education and practical help to improve their quality of life and build relationships that point the way to a hope-filled future for those who have not previously been given much reason to hope. Twiss and his wife started Wiconi with one seemingly simple concept in mind: “You can be Native and a follower of Jesus.”

That may not seem very groundbreaking, but for many it is, since the relationship between Christianity and Native peoples here in North America has never been a particularly good one. Pastor and author Mark Buchanan writes about the arrival of the “people of the Black Book” in what is now Vancouver, British Columbia:

The Tswassens have a prophecy 500 years old. One of their ancient holy men foretold that a people pale as birch would one day come from across the great water in large canoes. They would bring with them a Black Book. The Black Book was Truth, end to end, a gift of inestimable good. The people lived for many years awaiting the prophecy’s fulfillment.

And then one day it happened. The big canoes— bigger than the Tswassens ever imagined—arrived. They teemed with people pale as birch. And, yes, they brought with them a Black Book.

Then the killings started. The Tswassens became an obstacle to the pale men, and the pale men slaughtered them, and those they didn’t slaughter they enslaved.

Given this history, and compared with the justified indignation that saturates the pages of classic accounts like Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Twiss’s book is surprisingly hopeful and gracious. He doesn’t skirt around history’s ugliness, but he doesn’t stop there either. He wants to show Native Americans and the rest of us that Native culture isn’t antithetical to following Jesus; rather, the Gospel can be incarnated in Native forms just as easily — and perhaps even more so — than it has been in Western culture. Native Christians don’t need to follow our cultural customs when it comes to church and worship, in other words; instead, they may be better off without them.

But he isn’t out to sow resentment. Instead, he shows how the Gospel is what will bring true reconciliation between us and God, and between Native and non-Native groups. He even suggests that the testimony of Native Christians can be used in powerful ways around the world among others who have also been victims of terrible injustices. In his conclusion he writes:

If we, as Native followers of Jesus, are to emerge from our pain and absence to find our place in the Body of Christ, we need the love and help of all our brethren. Can we be seen as equal partners by the rest of the Body of Christ? Will we be allowed to develop new ways of doing church that honor God’s purposes for the creative expression of our cultures? Will new ministry partnerships and coalitions form? Will you help be a part of this wonderful process of reconciliation, restoration and release?