Not Irretrievable

Cornelius Plantinga, in his book Not the Way It’s Supposed to Be: A Breviary of Sin, writes, “God hates sin not just because it violates his law but, more substantively, because it violates shalom, because it breaks the peace, because it interferes with the way things are supposed to be.”

The characters in the films of Wes Anderson, like the worlds they inhabit, are not the way they’re supposed to be. They’re a mess, as anyone who has watched those films knows. But there’s something about those lives and those worlds that draw us in, that make us feel just a little more understood in all of our individual and collective weirdness. In his introduction to The Wes Anderson Collection by Matt Zoller Seitz, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author Michael Chabon writes:

The world is so big, so complicated, so replete with marvels and surprises, that it takes years for most people to begin to notice that it is, also, irretrievably broken. We call this period of research “childhood.”

There follows a program of renewed inquiry, often involuntary, into the nature and effects of mortality, entropy, heartbreak, violence, failure, cowardice, duplicity, cruelty, and grief; the researcher learns their histories, and their bitter lessons, by heart. Along the way, he or she discovers that the world has been broken for as long as anyone can remember, and struggles to reconcile this fact with the ache of cosmic nostalgia that arises, from time to time, in the researcher’s heart: an intimation of vanished glory, of lost wholeness, a memory of the world unbroken. We call the moment at which this ache first arises “adolescence.” The feeling haunts people all their lives.

Everyone, sooner or later, gets a thorough schooling in brokenness. The question becomes: What to do with the pieces?

I think the characters in Wes Anderson’s films feel so familiar to so many of us precisely because we recognize them as fellow classmates in the school of brokenness. And it’s no accident that quirky works of art like The Royal Tenenbaums and The Darjeeling Limited resonate in ways that purely didactic books or sermons rarely do.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently, especially since watching The Psalms, in which Eugene Peterson and Bono discuss the links between art, honesty, and prayer. In a Christianity Today profile of the director of short film, David Taylor says, “God has designed us to take joy in making stuff with the creation and then making sense of that stuff. The arts are a fundamental way to be human. They’re rooted in the work of the triune God.”

Art is a powerful way of making sense of the good stuff in our lives, yes, but maybe more important is the power of art to make sense of the bad stuff – the fragmented pieces of our lives. In one of his books, Eugene Peterson asks, “Isn’t it interesting that all of the biblical prophets and psalmists were poets?”

With the prophets and psalmists of scripture, let’s be honest about the pieces. And let’s live with hope, knowing that though the world is not the way it’s supposed to be, in Christ our shared brokenness is not irretrievable.

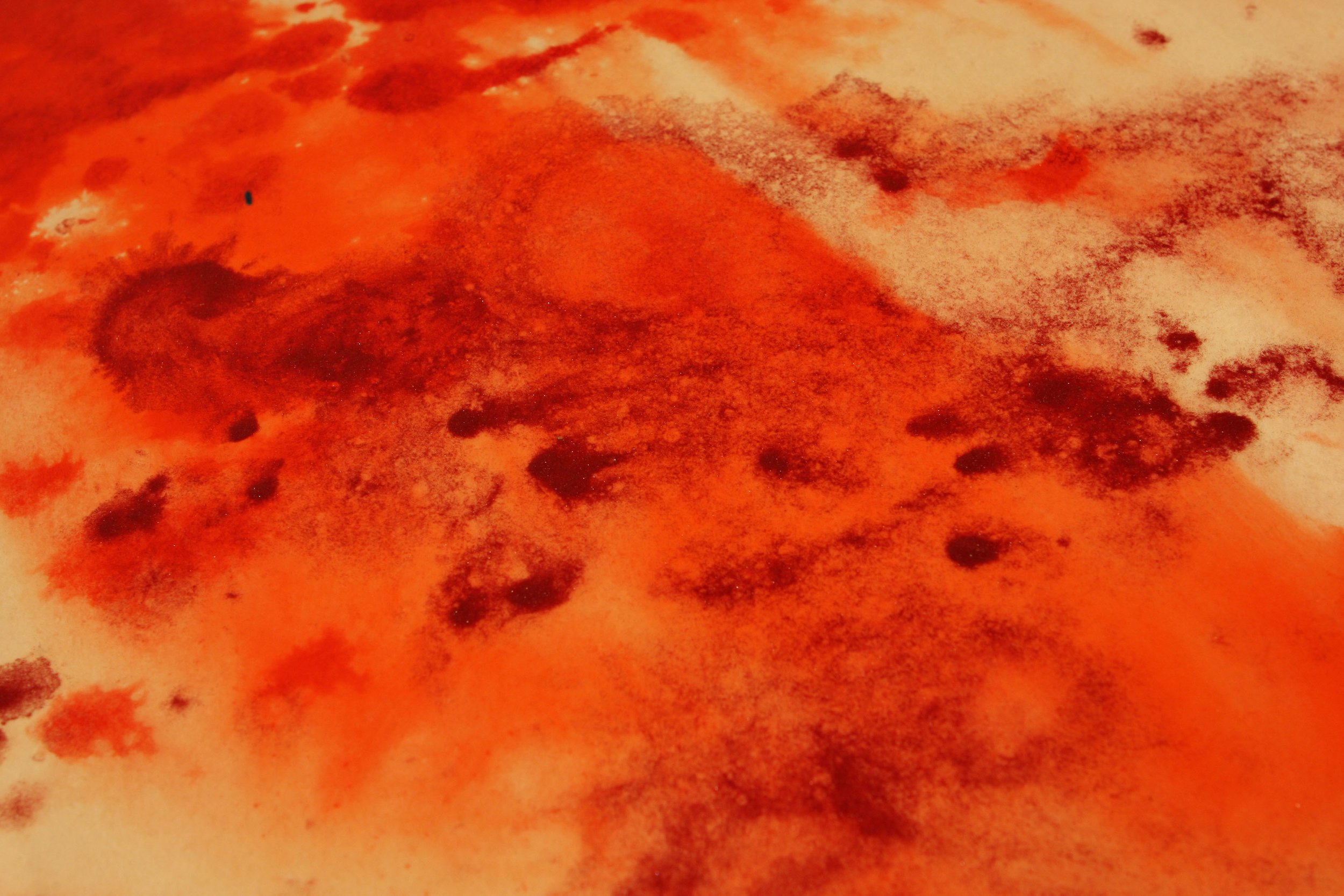

Artwork: Little Gidding by Makoto Fujimura (link)