New Series: The Lausanne Movement

A lot of the content that appears on this blog has to do with books I’m reading, events I go to, writing projects I’m working on, and other stuff I think might be worthwhile for the kind of folks who’d read a blog like this in the first place. That tagline at the top — “exploring the intersections of faith, development, justice & peace” — is as much for me as for you, reminding me to only post stuff that somehow fits within these set parameters (I make occasional exceptions in Repaso, my weekly roundup of all kinds of good stuff from around the internet).

From time to time I do a series of posts about a given topic that has something to do with those intersections. Two years ago this month, I did a six part series on the “Seek Social Justice” study produced by WORLD Magazine and the Heritage Foundation. Last April I ran a five part series on John Perkins and the Christian Community Development Association, focusing specifically on Perkins’ book, Beyond Charity: The Call to Christian Community Development. I’ve done a couple of other smaller series as well, like a three part look at Nicholas Wolterstorff’s book, Until Justice and Peace Embrace, which I posted last October.

These series have been meaningful for me, allowing me to reflect for a few weeks at a time on a particular thinker, theme or issue. And I’ve received positive feedback from them, which is always nice, and leads me to believe they’re helpful for others as well. So with all of that in mind, I introduce my next series…

Those of us in the evangelical stream of Christianity who are interested in one way or another in the intersections of faith, development, justice and peace, stand on the shoulders of a lot of faithful women and men who have gone before us. Not so long ago, there were significant roadblocks for those seeking to understand how an evangelical, missional Christian faith might relate to and inform one’s understanding of what it means to serve the poor, mediate reconciliation between actual enemies with weapons, seek the welfare of the city, and to otherwise contribute to the common good in meaningful and tangible ways. We’ve come a long way from the height of the fundamentalist-modernist divide in the early twentieth century North American church, and no, it hasn’t primarily been my generation that has brought this about; we’re just starting to reap the benefits of the faithfulness of others. Rather, I’d suggest it has a lot to do with the Lausanne Movement and some of its key early leaders, people like Billy Graham, Rene Padilla, Samuel Escobar, Carl Henry and John Stott.

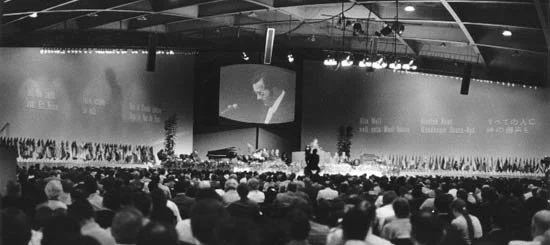

The First Lausanne Congress was held in Switzerland in 1974, with 2,700 participants from more than 150 countries. TIME called it “a formidable forum, possibly the widest ranging meeting of Christians ever held.” Here’s a three-minute video about that first gathering.

After the congress, a group of theologians and other Christian leaders drafted The Lausanne Covenant, with John Stott as its “chief architect” (more on Stott’s important contributions here). It’s a remarkable document, and it’s worth reading slowly and thoughtfully. For the purposes of this blog I want to highlight one section in particular, titled “Christian Social Responsibility.” Here’s how it reads (I know it’s a lengthy excerpt, but trust me, it’s worth it):

We affirm that God is both the Creator and the Judge of all people. We therefore should share his concern for justice and reconciliation throughout human society and for the liberation of men and women from every kind of oppression. Because men and women are made in the image of God, every person, regardless of race, religion, colour, culture, class, sex or age, has an intrinsic dignity because of which he or she should be respected and served, not exploited. Here too we express penitence both for our neglect and for having sometimes regarded evangelism and social concern as mutually exclusive. Although reconciliation with other people is not reconciliation with God, nor is social action evangelism, nor is political liberation salvation, nevertheless we affirm that evangelism and socio-political involvement are both part of our Christian duty. For both are necessary expressions of our doctrines of God and man, our love for our neighbour and our obedience to Jesus Christ. The message of salvation implies also a message of judgment upon every form of alienation, oppression and discrimination, and we should not be afraid to denounce evil and injustice wherever they exist. When people receive Christ they are born again into his kingdom and must seek not only to exhibit but also to spread its righteousness in the midst of an unrighteous world. The salvation we claim should be transforming us in the totality of our personal and social responsibilities. Faith without works is dead.

(Acts 17:26,31; Gen. 18:25; Isa. 1:17; Psa. 45:7; Gen. 1:26,27; Jas. 3:9; Lev. 19:18; Luke 6:27,35; Jas. 2:14-26; Joh. 3:3,5; Matt. 5:20; 6:33; II Cor. 3:18; Jas. 2:20)

There were three papers presented at that first Lausanne Congress that, according to pastor, professor and missiologist Dr. Al Tizon, “laid the theological foundation for evangelicals to engage wholeheartedly in ministries of community development, justice for the poor, advocacy for the oppressed and the transformation of society, alongside ministries of evangelism, personal discipleship and church expansion.”

Those three presentations were by Rene Padilla (“Evangelism and the World”), Samuel Escobar (“Evangelism and Man’s Search for Freedom, Justice, and Fulfillment”), and Carl Henry (“Christian Personal and Social Ethics in Relation to Racism, Poverty, War and Other Problems”).

Over the next three weeks, I’ll take each of those papers/presentations in turn, providing a bit of background on Padilla, Escobar and Henry, respectively, and drawing out some of the key concepts and arguments they make. I think you’ll see that what they had to say in 1974 is in many ways just as relevant to us today, if not more so. And just as they served to correct some of that generation’s blind spots having to do with the intersections of faith, development, justice and peace, they can do the same for us today. Following these three installments, if all goes well, I’ll take a look at some of the more recent contributions of the Lausanne Movement, specifically related to the 2010 Cape Town Congress.

I’m excited about this series. I hope you are too.