My Favorite Books of 2024

Here they are, friends, my favorite books of the year. They’re grouped here (loosely) by genre or theme, but appear in no particular order except, as usual, I saved my very favorite for last.

Thanks for another wonderful year of reading books and reflecting on them together. Advent peace to you and yours.

Tim

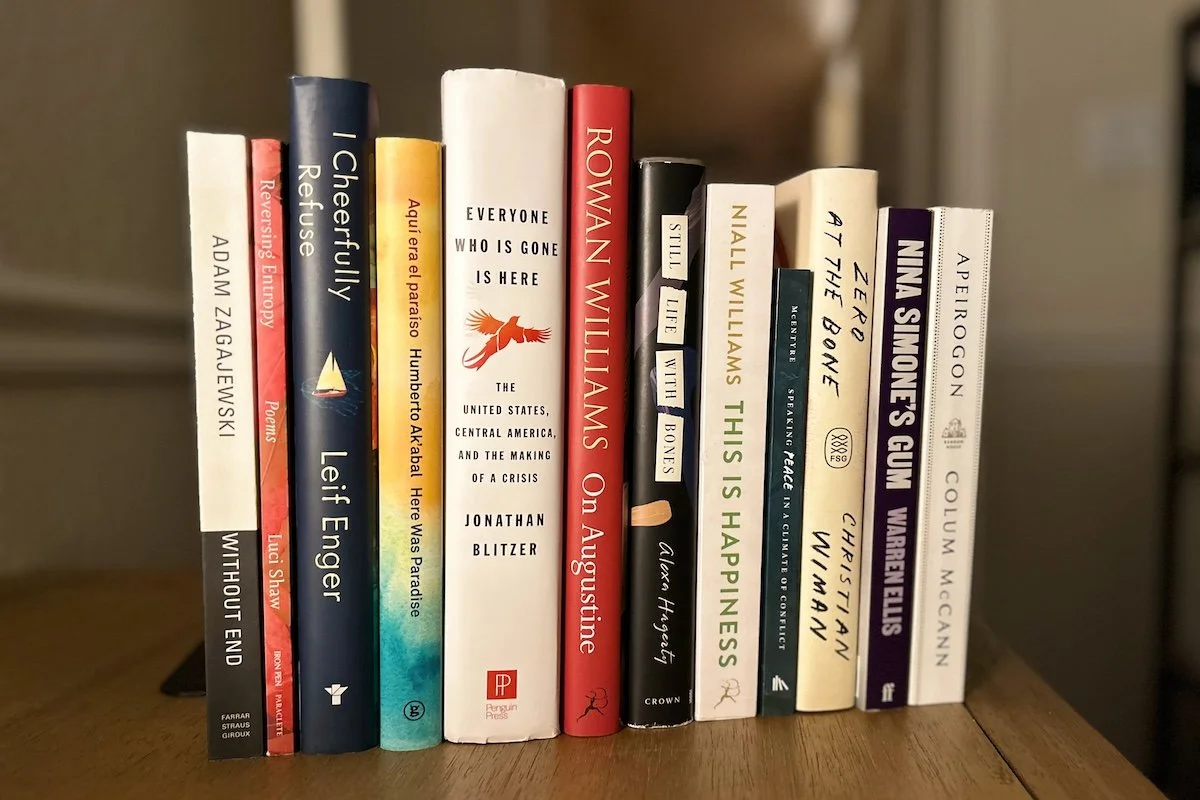

A joyful quasi-dystopian novel:

I Cheerfully Refuse: A Novel (Grove Atlantic)

by Leif Enger

When I reviewed this one in early summer I went out on a limb: “Of all the books I will eventually read over the course of 2024, I’m sure none will have a better title than Leif Enger’s novel I Cheerfully Refuse. The cover art, for what it’s worth, is just about perfect too. But my goodness, everything inside is even better.” I stand by it.

The bulk of the book takes place out on the water, in Rainy’s sailboat and in other vessels which shall not, for now, be named. There’s a bassline running through the book—literally and figuratively—and a desperate search for a lost manuscript. And I suppose the obvious way to think of all this is in terms of an adventure story. But when I reflect on the ways the novel made me feel, I return first to the humane warmth of the characters, their defiant joy against all odds.

Which is to say, Enger is skilled at writing about quixotic voyages in sailboats. But he’s at his best when he inhabits the language of grief and longing, writing believably about the bonds of love and the tenacity of hope.

Read more here.

A novel containing multitudes:

Apeirogon: A Novel (Random House)

by Colum McCann

The title comes from the geometric term for “a shape with a countably infinite number of sides.” A pretty good way of describing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, to be sure. But this novel is about so much more than that. It’s about Rami and Bassam, two real-life fathers divided by just about everything, but united in the worst of ways: they both buried a daughter. It’s also about migratory birds and slingshots and drones and rubber bullets and suicide bombings and checkpoints and dehumanization and grief and, yes, absolutely, hope.

In the middle of the book, we find ourselves at the Cremisan monastery on a hillside near Bethlehem:

“. . . on an ordinary day at the end of October, foggy, tinged with cold, to listen to the stories of Bassam and Rami, and to find within their stories another story, a song of songs, discovering themselves—you and me—in the stone-tiled chapel where we sit for hours, eager, hopeless, buoyed, confused, cynical, complicit, silent, our memories imploding, our synapses skipping, in the gathering dark, remembering, while listening, all of those stories that are yet to be told.”

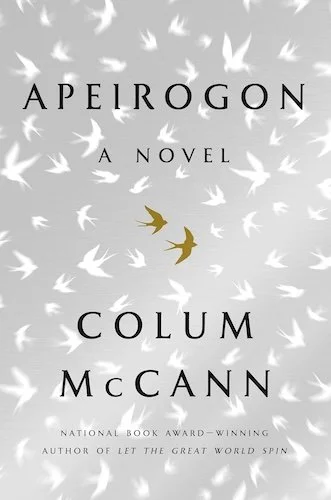

A (readable!) history of the church:

The Story of Christianity, Vols. I & II (HarperOne)

by Justo González

This two-volume history of the church is nearly 1,100 pages long, so it takes some dedication to get through it. But González—a Cuban-American and Methodist historian of the church—writes with characteristic warmth, giving this book a degree of readability setting it apart from similarly well-researched tomes.

Read more here.

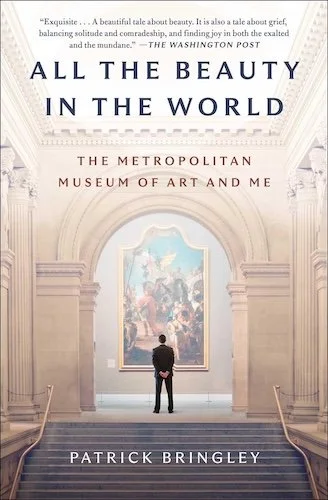

A surprising book about art and grief:

All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me (Simon & Schuster)

by Patrick Bringley

Bringley was one of the lucky few: he worked for the New Yorker. But when his brother was diagnosed with terminal cancer, he decided he needed a change of pace, or better, a change of scenery. He took a job as a guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—the most beautiful place he knew—and ended up staying ten years. This is that story.

“I responded to that great painting in a way that I now believe is fundamental to the peculiar power of art. Namely, I experienced the great beauty of the picture even as I had no idea what to do with that beauty. I couldn’t discharge the feeling by talking about it—there was nothing much to say. What was beautiful in the painting was not like words, it was like paint—silent, direct, and concrete, resisting translation even into thought. As such, my response to the picture was trapped inside me, a bird fluttering in my chest. And I didn’t know what to make of that. It is always hard to know what to make of that.”

See the painting here.

A book about a piece of gum (no, seriously):

Nina Simone’s Gum: A Memoir of Things Lost and Found (Faber & Faber)

by Warren Ellis

Yep, it’s a memoir. By an “an enigmatic Gandalf-like figure.” About somebody else’s piece of gum. And about so much more. Delightful and profound, both.

“Something shifted when others became aware of the gum’s existence. I thought about how many tiny secrets there must be out there in the universe waiting to be revealed. How many people have secret places with abandoned dreams, full of wonder.”

Read more here.

Winsome strategies for pursuing shalom:

Speaking Peace in a Climate of Conflict (Eerdmans)

by Marilyn McEntyre

We live in a culture of lies—one where untruths and half-truths are weaponized to divide us, to bewilder us, driving some of us to the brink of despair. McEntyre has written soberly but hopefully about these themes over the years, and gives them fresh consideration here. I found this book especially helpful as I think about stewarding relationships with friends who are “finding new beliefs,” as Christian Wiman put it, including some beliefs which trouble me greatly.

“In these pages I offer reflections that have emerged from my own work with words as a reader and writer and teacher, but also from my growing concern about what is happening to words as more and more of them become contaminated and turn into ‘triggers,’ as lies go unchallenged and honesty goes unrewarded—or is punished. I have tried to identify a number of strategies for maintaining clarity, integrity, and authenticity in the midst of the morass . . .”

Read more here.

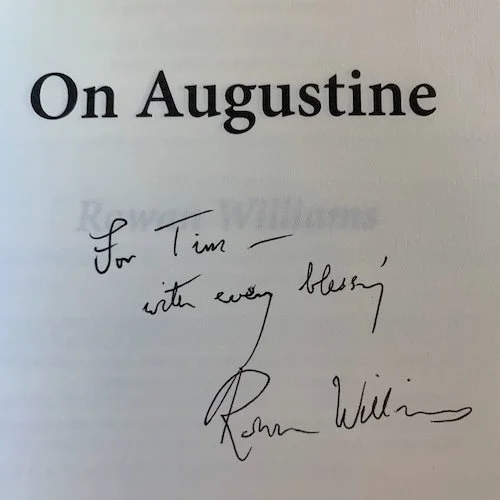

Subtle considerations of a polarizing saint:

On Augustine (Bloomsbury)

by Rowan Williams

For my doctoral program I’ve been thinking and writing about Augustine, paying particular attention to Rowan Williams as one of the most interesting interpreters of the famous Bishop of Hippo.

In this book—really a collection of lectures and papers spanning decades—Williams writes with subtlety and affection, exploring nuances in Augustine’s thinking we might otherwise overlook, and paradoxes we might be tempted a little too neatly to resolve. An excerpt I love from Williams’ sermon on the 1600th anniversary of Augustine’s conversion:

“The gospel still sounds through: at the heart of everything is a love that can bridge all difference and enmity, whatever the cost, however long the waiting, however hard and bloody the search for the lost. This is what is poured out for us and in us in Jesus; and we are set free by the assurance that nothing can deflect or weaken such a giving. . . . In the world we know, the world of widening gulfs, hardening enmity, violence and suspicion, this is good news we must never cease to proclaim. From over the wall which traps us in our various social paranoias we must hear the voice that cries, ‘Pick it up and read! Pick it up and read!’ Read the record of God’s mercy in Scripture and in the stories of the triumphs of his grace in the saints; read and be moved to trust and action and growth. ‘You know what hour it is, how it is full time now for you to wake from sleep.’”

A book no one else could possibly write:

Zero at the Bone: Fifty Entries Against Despair (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

by Christian Wiman

Wiman, whose work has comforted and confounded me over the years, has here set out to grapple—as only he can—with the mysteries and paradoxes of hope and despair, sorrow and joy. The book is comprised of fifty chapters of varying length, bracketed by a prologue and epilogue, both titled “Zero.” Some of the “entries” are nothing more than a single short poem. Others are longer essays. Others still read like a commonplace book. It’s a book that stays with you and invites rereading.

“People who have been away from God tend to come back by one of two ways: extreme lack or extreme love, an overmastering sorrow or a strangely disabling joy. Either the world is not enough for the hole that has opened in you, or it is too much. The two impulses are intimately related and it may be that the most authentic spiritual existence inheres in being able to perceive one state when you are squarely in the midst of the other. The mortal shadow that shadows even the most intense joy. The immortal joy that can give even the darkest sorrow a fugitive gleam.”

Read more here.

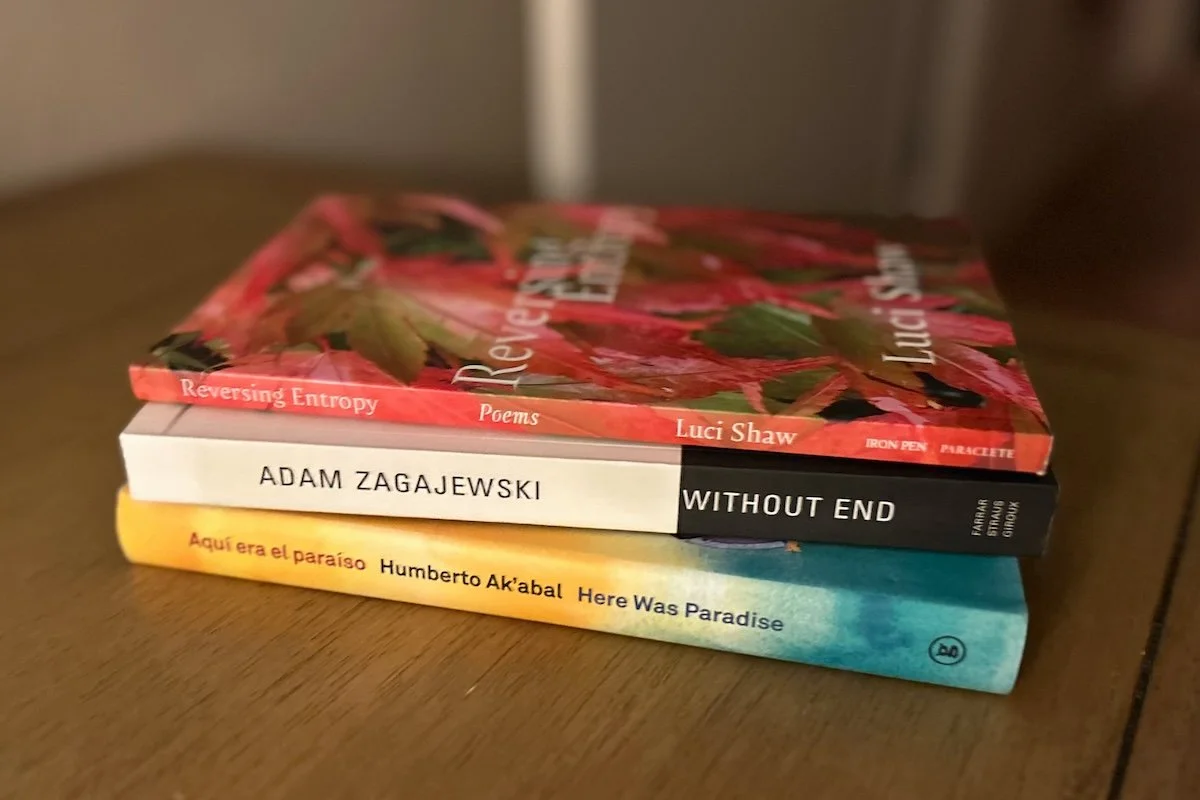

Four books of poetry:

Poets help us pay attention. They help us notice. Of the many poets I read this year, four in particular stand out. Here are just a few words about each of them.

Here Was Paradise / Aquí Era El Paraíso (Groundwood)

by Humberto Ak’abal

A K’iche’ Maya poet who died in 2019, Ak’abal wrote short vivid poems that transport me back to my childhood in rural Guatemala. Like this, and this.

A Fold in the Map (Nine Arches)

by Isobel Dixon

I learned of this South African poet in an anthology I included in last year’s list of favorites. The poems in this liminal book deal with twin losses in Dixon’s life: leaving her country of birth and the death of her father, an Anglican priest.

Reversing Entropy (Iron Pen)

by Luci Shaw

She’s 95 and still at it. Need I say more?

Without End (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

by Adam Zagajewski

For many years I’ve been acquainted with Zagajewski’s “Try to Praise the Mutilated World,” which found a wide audience in the days and weeks following 9/11. This collection from the late Polish poet is brimming with something I want to call luminous darkness, to borrow the title of a forthcoming book from a friend.

An audacious work of journalism:

Everyone Who is Gone is Here: The United States, Central America, and the Making of a Crisis (Penguin)

by Jonathan Blitzer

I reviewed this one for the Englewood Review of Books, and it turned out to be one of my very favorite books of the year. For the conclusion of my review I wrote:

“If collectively we are going to move past the indifference and the cruelty, we will need to learn the stories of actual immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. Which is to say, we will need to reject the caricatures. The best way to do that is to befriend people who have left homes and loved ones and livelihoods—almost always at great cost—to start over in a strange new land. But reading three-dimensional stories of such survivors is perhaps a good first step. In this emotionally charged election year, especially—one in which immigration will remain a key political wedge issue—every concerned citizen would benefit from reading this masterful, moving book.”

Forensic anthropology with a human touch:

Still Life with Bones: Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains (Crown)

by Alexa Hagerty

This one astonished me. For a book with the word “genocide” in the title, I was surprised by the one word that kept coming to mind as I read: tenderness. Hagerty is an anthropologist, and in these pages she works with forensic teams in Guatemala and elsewhere to better understand “how bones bear witness to crimes against humanity and how exhumation can bring families meaning after unimaginable loss.”

The work of forensic anthropology in countries with wartorn pasts is vital precisely because of decades of cruelty and carelessness. But those who devote themselves to this difficult work do so, day after day, with tenderness and care.

“Once I watched Cati measure a cranial fracture. When she finished, she ran her palm along the frontal bone, touching the skull just like you’d stroke a sick kid’s forehead. It was an action with no scientific purpose, an unmistakable gesture of comfort. She did it without thinking. I could have easily missed her fleeting touch, distracted by studying the fracture pattern. Or I could have seen it but not registered its significance because I already ‘knew’ what she was doing: analyzing a bullet trajectory, not comforting someone. My feeling of surprise could have dispersed without a trace. But I caught it and afterward noticed many subtle and ephemeral touches of care: adjusting the angle of bones to a more ‘comfortable’ position, patting a skull and saying ‘pobrecito.’”

My very favorite book of the year:

This is Happiness: A Novel (Bloomsbury)

by Niall Williams

“It had stopped raining.”

That’s the entirety of chapter 1, followed immediately in chapter 2 by vivid descriptions of the many ways rain had manifested itself in Faha since, well, forever. “It came straight-down and sideways, frontwards, backwards and any other wards God could think of,” our narrator tells us. “It came dressed as drizzle, as mizzle, as mist, as showers, frequent and widespread, as a wet fog, as a damp day, a drop, a dripping, and an out-and-out downpour.” That is, until now.

When a novel begins with writing this good, you don’t need to have a clue where the story is going. You’re just happy to be along for the ride. Months later, I’m still smiling. It’s my favorite book of the year.

“Books, music, painting are not life, can never be as full, rich, complex, surprising or beautiful, but the best of them can catch an echo of that, can turn you back to look out the window, go out the door aware that you’ve been enriched, that you have been in the company of something alive that has caused you to realise once again how astonishing life is, and you leave the book, gallery or concert hall with that illumination, which feels I’m going to say holy, by which I mean human raptness.”

Read more here.

Other books I read for the first time in 2024 and really, really liked:

Epiphany by Fleming Rutledge

A Little Devil in America by Hanif Abdurraqib

Tierra de Árboles by James Rodríguez

The Wound of Knowledge by Rowan Williams

The Rise and Fall of Dispensationalism by Daniel Hummel

Holiness Here by Karen Stiller

Telling Stories in the Dark by Jeffrey Munroe

Circle of Hope by Eliza Griswold

Drawn to the Light by Marilyn McEntyre

The Riches of Your Grace by Julie Lane-Gay

The Jubilee by John Blase

Want even more?? I have a list of all the books I read this year on the intentionally semi-hidden Reading page of my website. Favorites are given the star treatment. Ones I’ve written about are underlined and linked.

As always, thanks for reading. Tell me, what was your favorite book of the year?

Tim