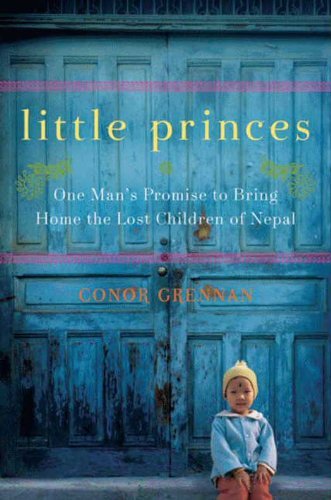

Little Princes

Conor Grennan never set out to be a hero. Indeed, how could he have known that what began as a sort of guilt-induced public relations stunt to appease his friends and impress girls would in fact radically alter the course of his life and the lives of countless others?

Little Princes is Grennan’s story, starting with his arrival as a volunteer at Little Princes Children’s Home outside Kathmandu, intended as a three-month humanitarian stop-over on the way to his real adventures elsewhere. But when he came to learn that many of the children in the orphanage – with whom he now shared a deep bond – were in fact no orphans at all, it was something impossible to ignore.

What ensues, in a book equal parts memoir, cultural study and love story, is Grennan’s account of trekking through the Himalayas, battling nature and fatigue, facing off against traffickers, forming unlikely alliances, falling in love, and ultimately helping to reunite nearly all of these children with their parents in Humla – the far-off, nearly inaccessible part of the country from which they had originally come.

The story is rooted in Nepal’s decade-long civil war, in which Maoist rebels – unable to operate in or near the capital, which remained under the control of those loyal to the king – targeted poor families in rural areas for conscription into their army, often abducting young children. In this context, poor families were presented with the opportunity to pay a large sum of money to a man who would take their children out of harm’s way and into Kathmandu where, he assured them, they would be well cared for. Out of desperation and wanting a better future for their children whatever the cost, many parents agreed.

Unfortunately, this man was in fact a trafficker, and while some children eventually ended up in orphanages like Little Princes Children’s Home where they received love and care, many others remained on the streets, completely vulnerable to disease, hunger, and worse.

Today, through an organization Grennan cofounded called Next Generation Nepal, trafficked children are placed in safe transitional homes where they are cared for and educated until, ideally, they can be reunited with their families. NGN excels at the child- and family-level, and one can only imagine what it must be like for these families to be reunited.

But Grennan’s approach is clearly no panacea. It would take a lot more than this to tackle the root causes of trafficking in Nepal at any sort of a structural level. Doing so would require a systematic overhaul of what appears to be a largely corrupt law enforcement system that fails to protect the vulnerable, as well as the equally important and enduring issue of rural poverty, which makes these families easy targets for traffickers in the first place.

But again, as Grennan makes clear, he never set out to save the world. His connection to Nepal is a personal one, and because of his work – and through the stories in his book – many readers will feel inspired and compelled to find ways to support these families who have endured so much. One certainly hopes that structural change will come to Nepal in time, but at least for 300 children and their families, being reunited is more than enough for now.

This review was originally published in PRISM, a publication of Evangelicals for Social Action.