I Cheerfully Refuse

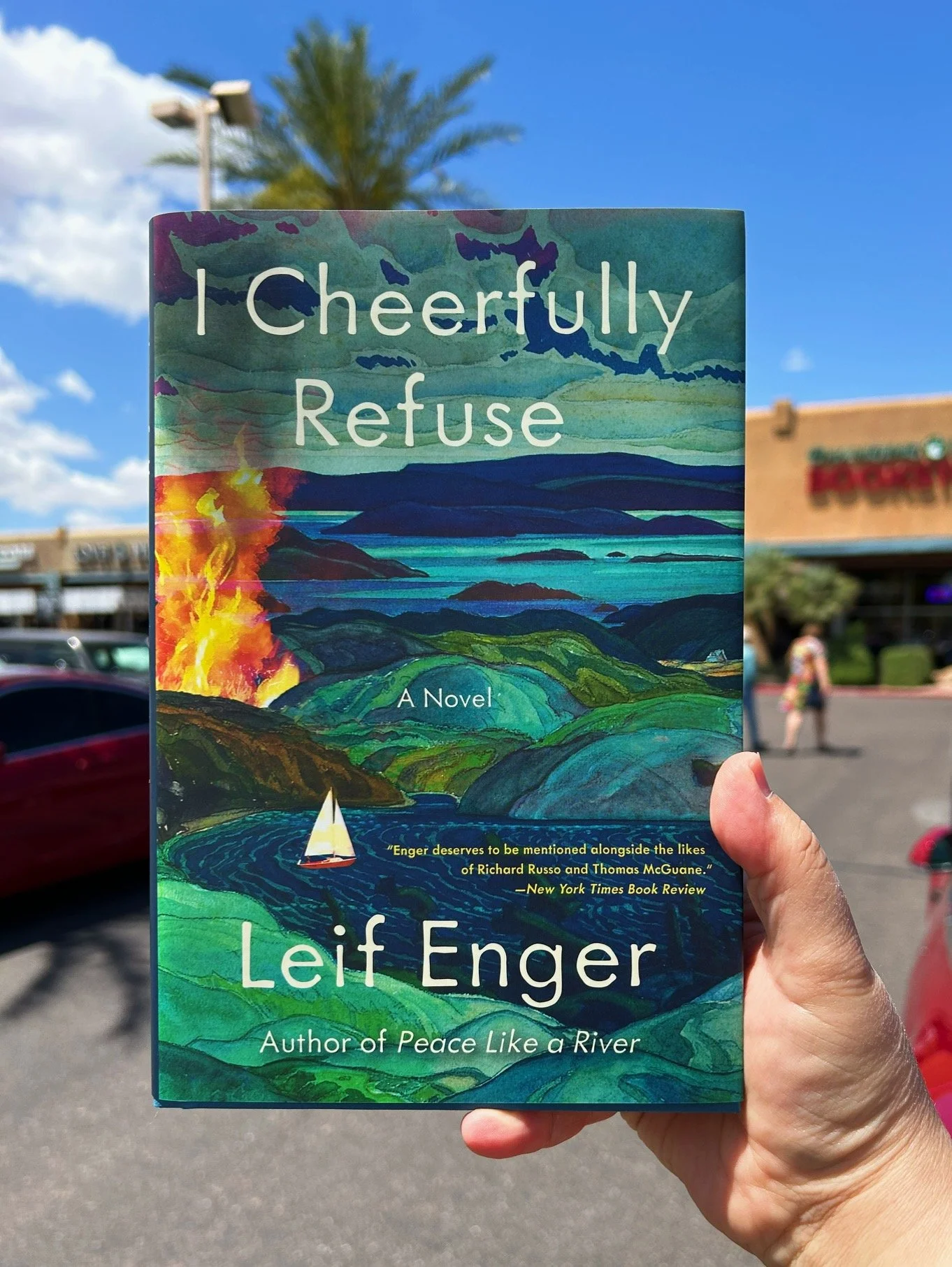

Of all the books I will eventually read over the course of 2024, I’m sure none will have a better title than Leif Enger’s novel I Cheerfully Refuse (Grove Atlantic). The cover art, for what that’s worth, is just about perfect too. But my goodness, everything inside is even better.

Enger says he sat down to write this book at the beginning of COVID lockdown—as good a time as any, I suppose, for a writer to dream up the dystopian landscape where Rainy and Lark, our narrator and his bookselling wife, make the best of bad times on the shores of Lake Superior.

In his conversation with Jonathan Rogers on The Habit podcast, Enger recounts learning a while back that the bottom of Lake Superior has a temperature of 38° F, and that dead human bodies generate gasses and begin to rise when they hit 39° F. When it came time to inhabit a near-future dystopian mindset, he was fortunate enough to recall that macabre fact. “If you think of that, and you’re a novelist,” he says, “there’s something the matter with you if you don’t use it.”

The kind of dystopia that Enger imagines isn’t very far-fetched. There’s no nuclear annihilation, no pandemic, not even a suspension of the constitution (as far as we know). Instead, it seems the country has just sort of drifted—a situation in which temperatures have ticked up a degree or two, currencies have plummeted, literacy has all but fallen by the wayside, and sixteen elite families on the coasts own virtually everything. (If I ever have the good fortune of chatting with Enger, I’m going to ask him if El Salvador’s Fourteen Families provided the inspiration for that last detail.)

Despite all the apocalyptic stuff, Enger had fun writing this book, no doubt about that. Rainy’s narration is peppered with aphorisms, turns of phrase, and characters with names and backstories that delight and spark wonder.

At one point, his wife’s mildly subversive bookstore is targeted by a man who came from 400 miles away to toss a homemade bomb through the store’s window. This “young patriot” had previously, for reasons lost to memory, changed his name to Large Beef. Whatever life skills Large Beef possesses, bomb-making isn’t one of them. The bookstore bomb is “stuffed with red-dot gunpowder” but lacks a detonating mechanism. It’s a dud. “I was new to ironies and watched them pile up,” Rainy says. “If Large Beef could read he might’ve made a working bomb, but would a reading Beef want to?”

The bulk of the book takes place out on the water, in Rainy’s sailboat and in other vessels that shall not, for now, be named. There’s a bassline that runs through the book—literally and figuratively—and a desperate search for a lost manuscript. And I suppose the obvious way to think of all this is in terms of an adventure story. But when I reflect on the ways the novel made me feel, I return first to the humane warmth of the characters, their defiant joy against all odds.

Which is to say, Enger is skilled at writing about quixotic voyages in sailboats. But he’s at his best when he inhabits the language of grief and longing, writing believably about the bonds of love and the tenacity of hope.