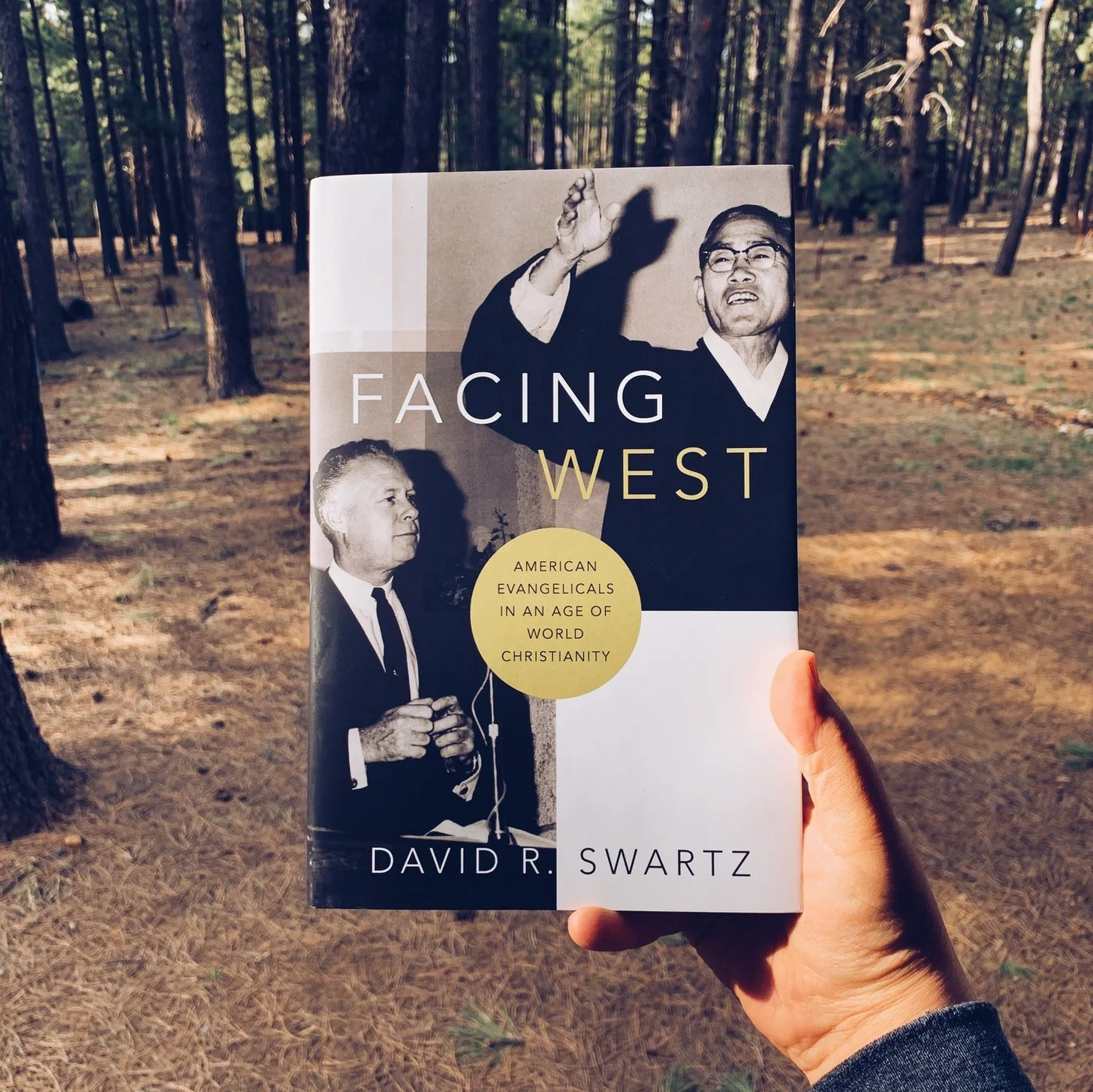

Facing West

David R. Swartz is one of those rare scholars whose work I’m always eager to read. A history professor at Asbury University with a Ph.D. from Notre Dame, Swartz’s first book was Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism (Penn Press).

In my review, I described it as “a carefully researched and exceptionally written work of history about a really fascinating period in time. … [Swartz] argues that progressive evangelical activists laid the very groundwork for political engagement that the Religious Right soon employed for their own far different agenda.” (FWIW, I also listed Moral Minority as one of my favorite books of 2012.)

Swartz’s second book, Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity (Oxford University Press), serves as a natural follow-up – and it doesn’t disappoint. Here, Swartz (re)narrates the ways in which North American evangelicals have been – and continue to be – shaped by believers from the Global South, often in unpredictable ways. He also reveals that the historical narratives we’ve inherited sometimes tell only half the story.

Early in the book, we’re presented with two drastically different versions of the founding and growth of the humanitarian giant World Vision. When I worked for Big Orange (as I affectionately call it) between 2009 and 2012, I learned all about Bob Pierce. I learned about his relief work in Korea at the time of the war, how he started mobilizing support for orphans there, and how his tenacity and compassion eventually led to the founding of the organization. I memorized Pierce’s words: “Let my heart be broken by the things that break the heart of God.”

But that’s just one half of the story. The other side – the story told in South Korea to this day – emphasizes the role of someone else: a Korean pastor named Kyung-Chik Han. Far from merely serving as Pierce’s translator, Han was, for all intents and purposes, a co-founder of the organization. (See Swartz’s April 2020 cover story for Christianity Today for more of this story.)

Those dual narratives set us up for everything that follows in the book. In later chapters, we read about the competing agendas at the global Lausanne gathering in 1974, Pentecostalism in Guatemala, and fault lines within the Anglican Communion over biblical authority and sexual ethics. In each case, we’re challenged to ask ourselves whether we understand the whole story – and the degree to which our view is hampered by culturally conditioned blind spots.

One of the significant figures in Facing West is René Padilla, an Ecuadorian-born theologian who died this week at the age of 88. At the Lausanne gathering and through his writing and teaching over the years, Padilla advocated for what he called misión integral, a holistic approach that remains the primary lens through which I view my work with 1MISSION and the mission of the church more broadly. I’m indebted to him.

Incidentally, Padilla’s daughter, Ruth Padilla DeBorst, reviewed Facing West for the Christian Relief, Development, and Advocacy journal last year. In her review, she synthesizes the book’s core themes well and offers a gentle critique. I hope you’ll read Swartz’s book but I’d also encourage you to also read what Padilla DeBorst has to say.