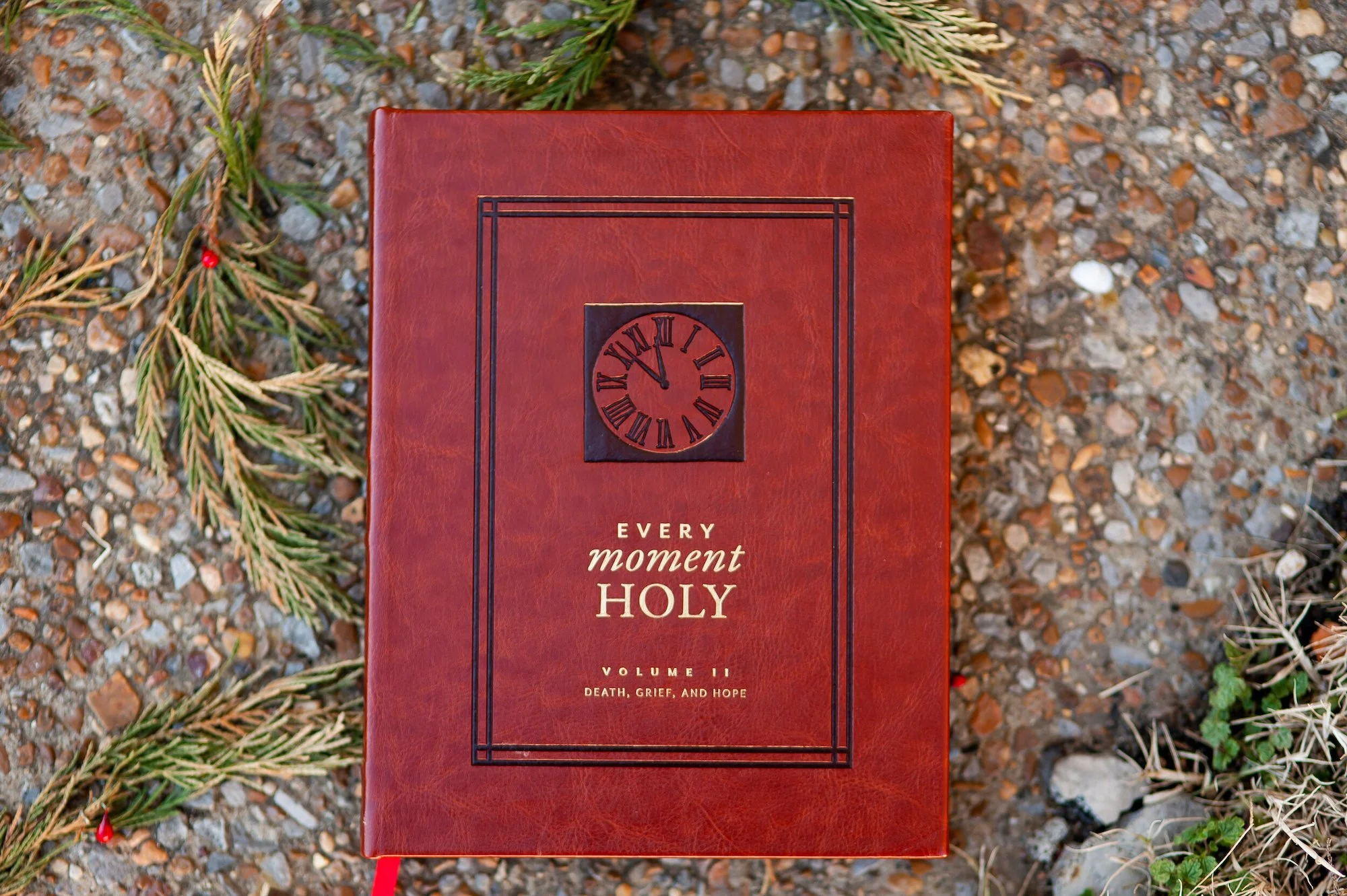

Every Moment Holy, Vol. II

Here’s my favorite thing about the original edition of Douglas Kaine McKelvey’s Every Moment Holy: the poetic yet earthy particularity of the liturgies.

On a weekly and daily basis, and for some of the biggest moments of life—weddings, funerals, baptisms—we Anglicans lean heavily on the Book of Common Prayer. The confessions and collects, the Eucharistic prayers and the prayers of the people, they give voice to the longings of our hearts in simple, biblical, true language. But what about those in-between moments: quotidian, maybe, but no less significant? They may be joyful: feasting with friends, gardening, going on vacation. Or they may not: insomnia, work deadlines, news-induced anxiety.

All these moments matter to us. All these moments matter to God. Ergo, Every Moment Holy.

Here, in volume two (also from Rabbit Room Press), McKelvey leans especially into the dark stuff. He does so not in despair, but—as the Prayer Book puts it—“in sure and certain hope of the Resurrection.”

In the Foreword, he calls us to reclaim “a more robust theology of dying” and to reexamine “the ways in which we relate to and care for the dying and the grieving among us.” McKelvey writes:

Such care should not be the sole purview of therapists and practitioners of medicine, after all—though they each have their valuable places. But neither of those fields is generally equipped to offer spiritual shepherding, nor compassionate community, nor to infuse the journeys of the dying and grieving with the great and central hope contained in the sweeping story of God’s redemptive works across history and into eternity—namely, that death is not the end, that all creation will be made new, the children of God resurrected unto eternal life in glorified physical bodies in which we will live and play and take joy, all to the glory of God, in community, in creativity, in worship, in wonder, and in celebration. Remembrance of this story, and of how our own deaths find their context in it, is one of the great gifts the church has been given to steward, and a gift that we ought to continually offer to one another. It is the best hope in all of creation.

The best hope in all of creation. We need it. I need it. Flimsy substitutes will not do.

Just as in volume one, the liturgies here are written for very particular moments. In some cases, the title alone is enough to pierce the heart: “For the Morning of a Medical Procedure,” “For Those Facing the Slow Loss of Memory,” “To Stir Courage in a Child Facing Death,” and “For Removing One’s Wedding Ring,” to name a few.

Whatever the particulars of our lives—and the particulars of the lives entrusted to our care—all too many of these liturgies will, at one time or another, speak to our distress while anchoring us in the love of the Suffering Servant who has died, is risen, and will come again to make all things new and to wipe away every tear.

“These prayers and liturgies are offered in light of that eternal hope,” McKelvey writes, “and in the hope that they might serve the Body of Christ, encouraging us to give ourselves more fully to the experience of our present sorrows in light of those unshakeable joys to come, to better learn what it means to nurture, serve, encourage, and carry one another, and ultimately to reclaim a greater sense that these journeys of dying, caretaking, and grieving are holy moments to be experienced in communion with God, and in fellowship with one another, just as any other facet of our discipleship.”