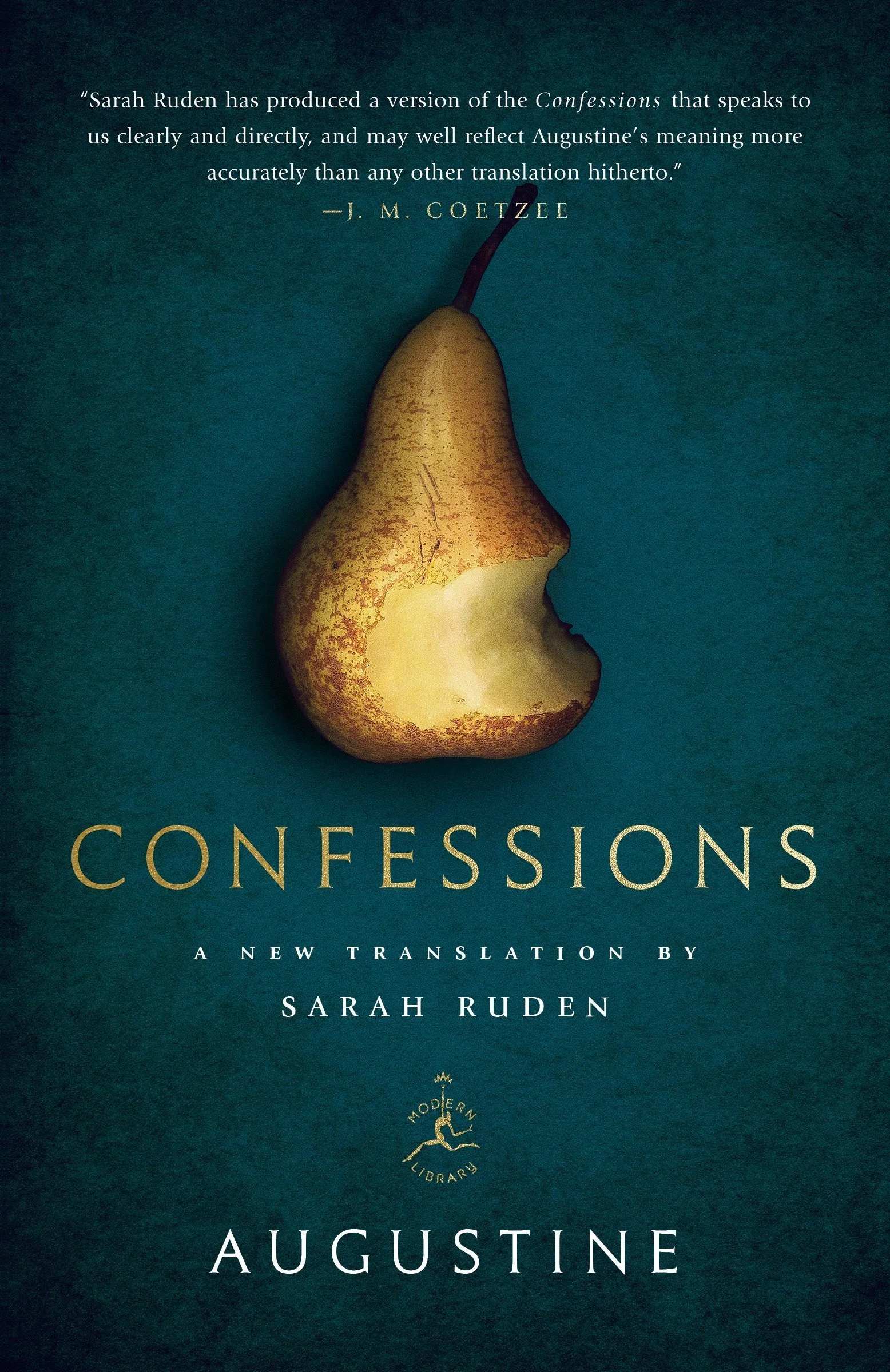

Confessions

The first time I read Augustine’s Confessions, I was 23 and living in Cambodia. The bright young daughter of a colleague saw me reading it and asked what it was about. I don’t remember what I told her; I only recall that she wasn’t impressed. To be fair, I didn’t have much of a frame of reference for Augustine or Confessions at the time, besides the obvious: the man was a saint and the book was a classic. Good enough for me.

By my second go-around, I was 31. Different passages resonated with me; I had a better feel for what Augustine was searching for, and I had a heightened awareness of my hunger for those same things. I may have even been able to hold borderline intelligible conversations about some of it. And of course I committed certain lines to memory, as one does: “You stir man to take pleasure in praising you, because you have made us for yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.”

Now, at 40, I’m slowly making my way through Sarah Ruden’s newish translation of Confessions from Modern Library. And I find myself discovering new passages, as if for the first time. I’ve been especially enthralled by so much of Book 10, where Augustine reflects on the possibilities of self-knowledge—always in relation to the knowledge of God. This is the part of the book where he also considers the mystery of memory.

Memory is housed, Augustine tells us, in “spacious palaces,” a “huge receptacle,” an “immense royal court.” He continues: “The power of memory that I’m writing about is tremendous, my God—intimidatingly great: an extensive, a boundless innermost recess. Who has ever gotten to the bottom of it?”

For Augustine, the stewardship of memory is a fundamental spiritual discipline. We simply cannot know God, much less ourselves, without the cultivation of it. “What we do is take the things memory holds in random and arbitrary arrangements and bind them together, as it were, by thinking about them, and care for them by paying attention to them.”

He could not have known it at the time, but Augustine is describing what scientists today call synaptic plasticity, the truly amazing ability God has given us to wire and rewire the connections in our brains. This is how memory works.

As the Christian psychiatrist Curt Thompson writes in Anatomy of the Soul (Tyndale), “[O]ur memories are not static things that sit inertly in the safe-deposit box of our minds. They are changed by the very circumstantial information in which we both encode and recall the events in question.”

And we encode those memories, Thompson tells us, through the telling and retelling of stories. “Loving God is autobiographical,” Thompson writes. “It is about remembering our past and anticipating our future. It is about a God who will not be kept at a distance but uses each of our stories to confront, terrify, comfort, convict, and woo us.”

This is precisely what we see in the Confessions. God acts; Augustine responds.

Augustine doesn’t comprehend everything that’s happened in and to and around him, nor does he claim to fully understand the work of God; there’s always a degree of mystery involved. So he wrestles. He wonders. He stewards the gift of memory in all its pain and beauty. Through it all, of course, he prays. He never stops bringing the totality of his life before God in prayer.