A Whole Different Ball Game

I grew up devouring Ken Burns’ 18.5-hour Baseball documentary series. My grandparents in New Jersey taped all nine episodes when the series aired on PBS in September 1994 and sent them to me in Guatemala. Those VHS tapes may not work anymore, but whenever I’ve moved they’ve come with me. They remain prized possessions.

It was in that documentary that I first encountered, through interviews, people whose books I would later read: Roger Angell, Buck O'Neil, Doris Kearns Goodwin, George Will, Bud Selig, John Thorn, Thomas Boswell, Donald Hall.

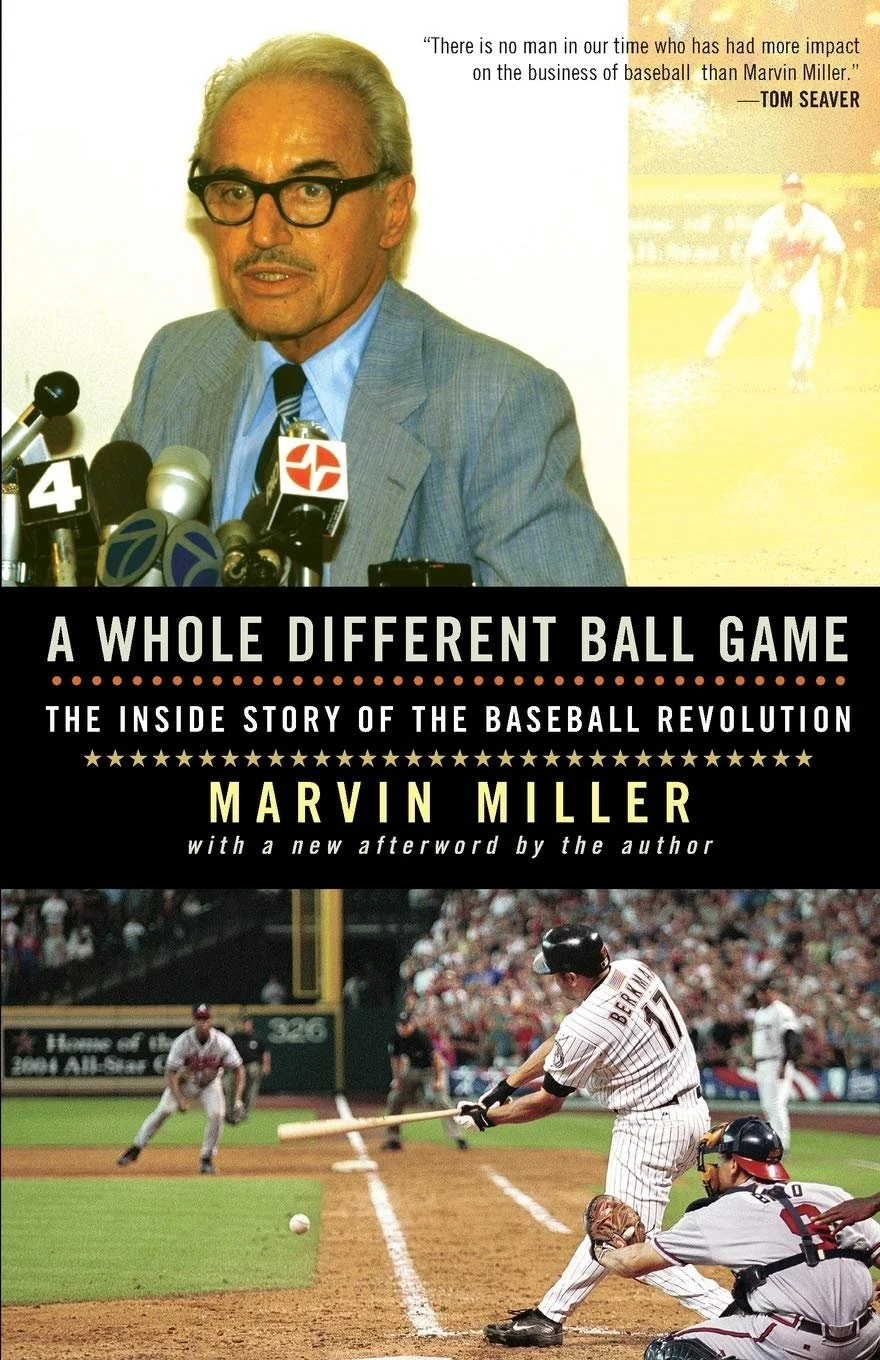

Now, with A Whole Different Ball Game (Ivan R. Dee; 1991, 2004), we can add Marvin Miller to the list. I like to read a baseball book in the spring, and given the lamentable situation vis-à-vis the MLB lockout, I thought I’d finally pick up this memoir by the former executive director of the players’ union to better understand the fraught history of labor relations in baseball.

I’m still in the early going, but the first few chapters of the book survey the events that shaped Miller into the man who would be so instrumental in bringing about “a whole different ball game.”

Here’s one interesting example. When Miller initially thought of leaving his prestigious post as chief economist for the United Steelworkers in Pittsburgh to take the helm of the fledgling Players Association in New York, his colleagues wondered if he’d lost his mind. The union he worked for was large and powerful, doing important work. Unions in sports were a joke. And Willie Mays and Sandy Koufax weren’t exactly blue collar workers. So much for a moral commitment to the underdog, right?

But Miller soon found an answer that conveyed more than any rational explanation ever could. “I grew up in Brooklyn,” he would say, “not far from Ebbets Field.” He loved going to games, “one of the countless kids who felt intimately connected to the fortunes of the Dodgers,” who could “recite the vital statistics of every Dodger—and of most of their competition too.” He was a baseball fan. And as a baseball fan, he loved baseball players.

Miller was 33 when Walter O'Malley took control of the team and 40 when O’Malley moved the Brooklyn Dodgers as far away as he possibly could: to Los Angeles. For O’Malley, it was a lucrative business move. To the fans, it was a betrayal. Later, then, when Miller became executive director of the Players Association, his childhood Dodger fandom—and O'Malley’s subsequent betrayal—had a lot to do with it.

Time, place, people: the forces that made Marvin Miller who he was. Forces that shape every one of us.