A History of Violence

When people learn I was born and raised in Guatemala, I have come to expect one of two reactions. First, wide eyes and a “Wow, that must have been crazy.” Second, though far less frequently, maybe a story about visiting the colonial city of Antigua or of volunteering at an orphanage near Lake Atitlán once. And that’s about it.

Even though Central America is very close to us geographically, and though our histories are bound up together, for various reasons most people in the United States know very little about the three countries in the so-called “Northern Triangle” of Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

I’ll be honest: it’s kind of understandable. To the extent that any of us follow international news, the headlines and stories coming out of Central America are for the most part bleak. There are places in the region people like us simply don’t go, and therefore, lots of stuff people like us simply don’t understand.

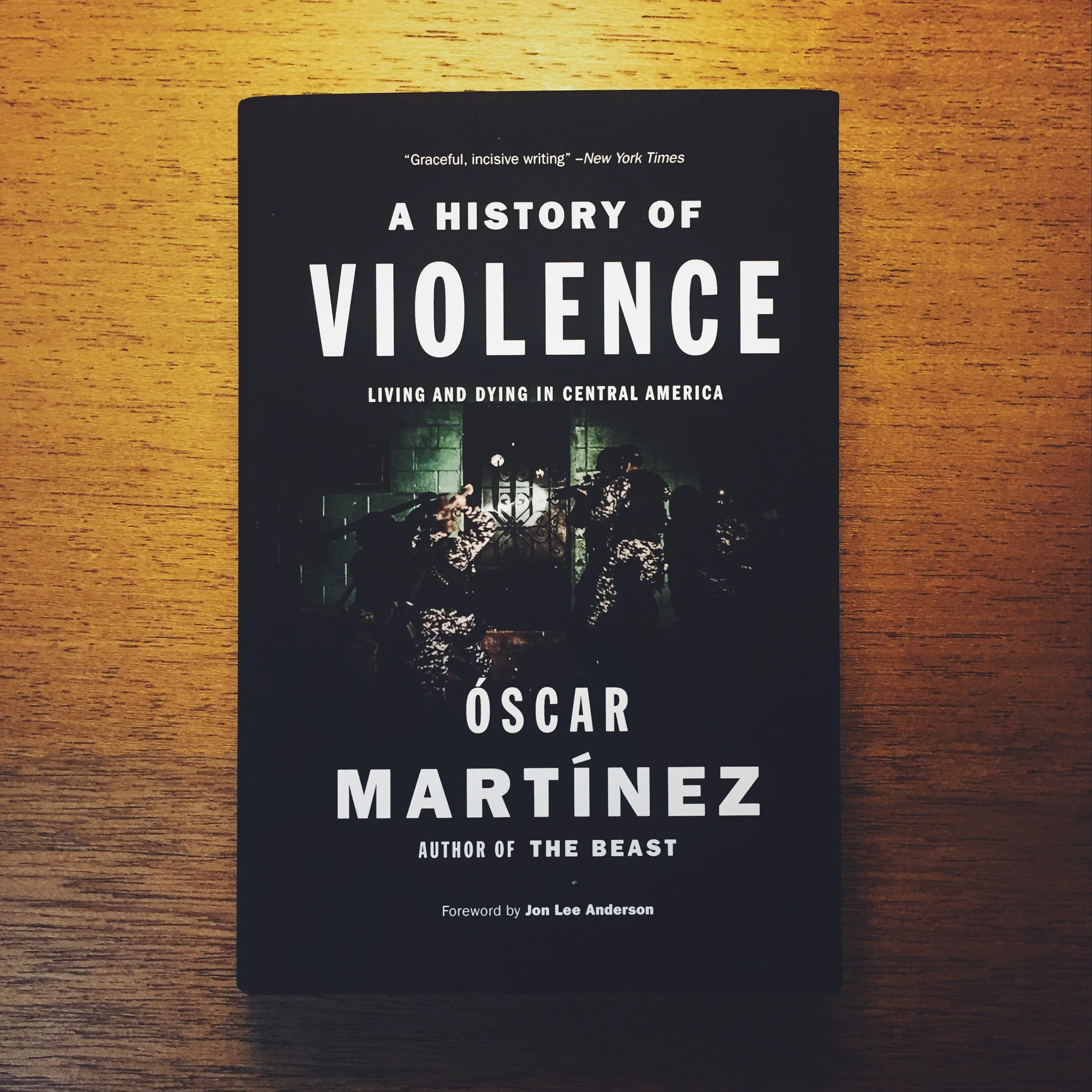

And that’s where Óscar Martínez comes in. A Salvadoran journalist with the independent El Faro digital newspaper, he is a courageous reporter with mind-boggling tenacity. First in The Beast, about the Central American migrants who ride atop northbound trains through Mexico, and now in A History of Violence, Martínez introduces us to real-life characters we couldn’t have dreamed up on our own.

The chapters that comprise History began as standalone pieces of reportage, which explains why this collection feels a little repetitive and disjointed at times – and it’s worth noting that the book was translated and edited by people other than Óscar Martínez, so that’s not necessarily a knock on him.

Despite the book’s flaws, I read this one attentively, exploring new layers of Guatemala, a country and a people I love, and about El Salvador and Honduras, two countries I’ve never visited and about which I know far less. It is not a particularly hopeful book, so if you’re looking for that, you’ll need to turn elsewhere. But what the book does is pull back the veil on the violence and terror that drive so many to flee their homes – and it reveals what life is like for those men, women, and children who, for reasons of their choosing or not, remain in gang- and cartel-controlled territory.

As heavy as it is, I’m not left completely bummed out after reading History. For one thing, I am once again inspired by Martínez’s determination to tell the truth when all the incentives are aligned to keep his mouth shut. I wish those who flippantly decry “the media” could meet journalists like this; I’m sure they’d be led to nuance their critiques. I am also heartened to learn about the brave police officers, prosecutors, judges, and elected officials who – again, despite very strong incentives – seek to uphold justice in this region.

I continue to pray for my friends in Central America, just as I continue to pray for those who have betrayed them. And I give thanks for those heroes who, as a way of life (literally), work for the day when justice and peace will embrace.