A Day with Rowan Williams

One evening late last year, I caught wind of a gathering that would soon take place at an abbey in a canyon in Southern California. Rowan Williams, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, would be giving some lectures on Augustine. The event would be free but not, apparently, well-publicized.

I looked at our calendar. The date was clear. I started making plans.

The day before the event, I drove out to Anaheim. After checking into my hotel, I met up with some friends in nearby Westminster, where we sat around a bonfire before making our way to a roadside taco stand for some of the best al pastor tacos of my life.

The next morning, I woke early and ended up in Laguna Beach. I walked around for twenty minutes, breathing in the salty sea breeze. And then I drove up into Silverado Canyon to spend the day contemplating wonders of a different kind.

St. Michael’s Abbey is a Norbertine monastery founded sixty years ago, which moved to a gleaming new facility in recent years. I had hoped the lectures would be held in the vaulted, stained-glass church, but in fact they took place in a nondescript conference room. (Midday prayer in the church—with chanted psalms and prayers—was a nice consolation prize.)

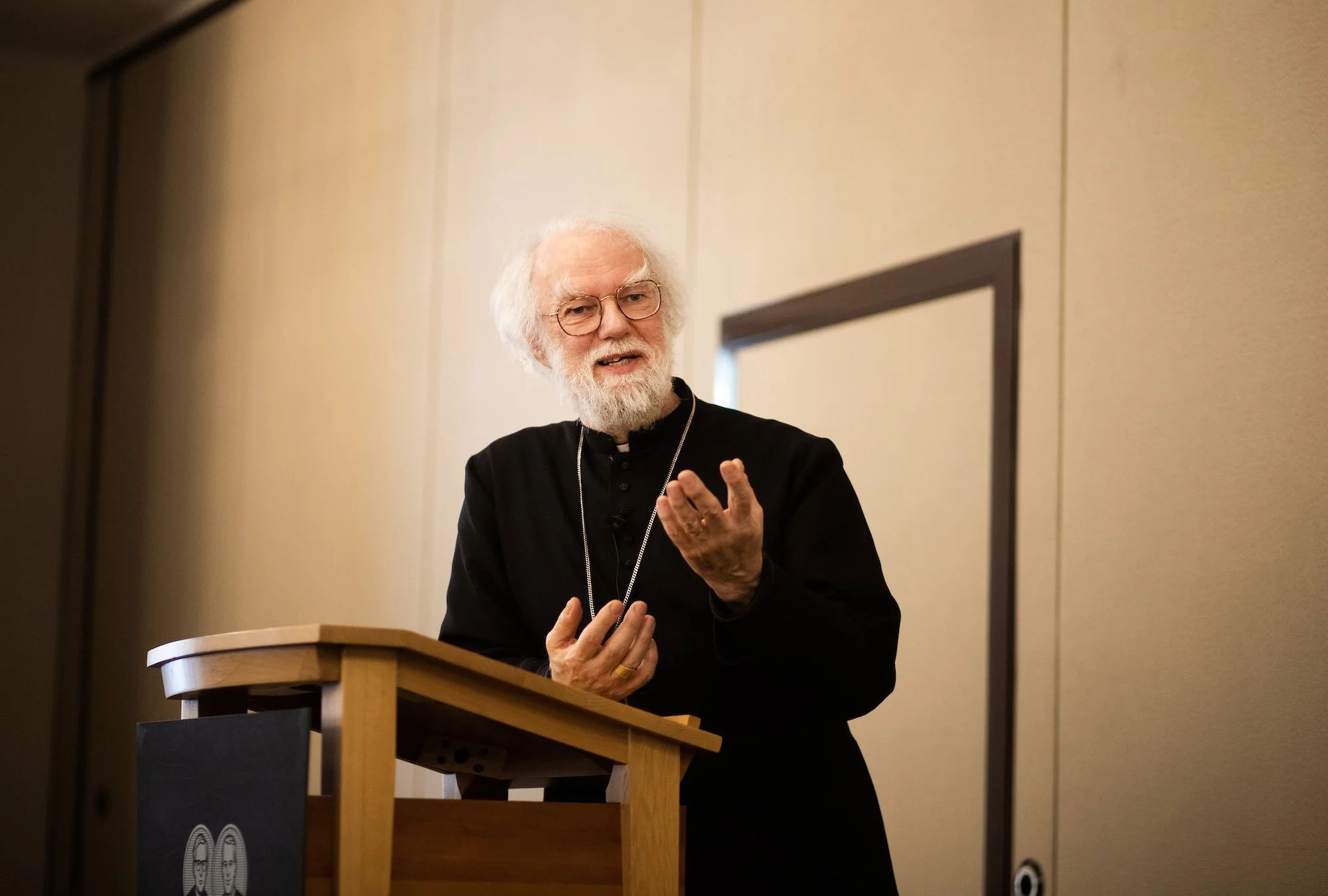

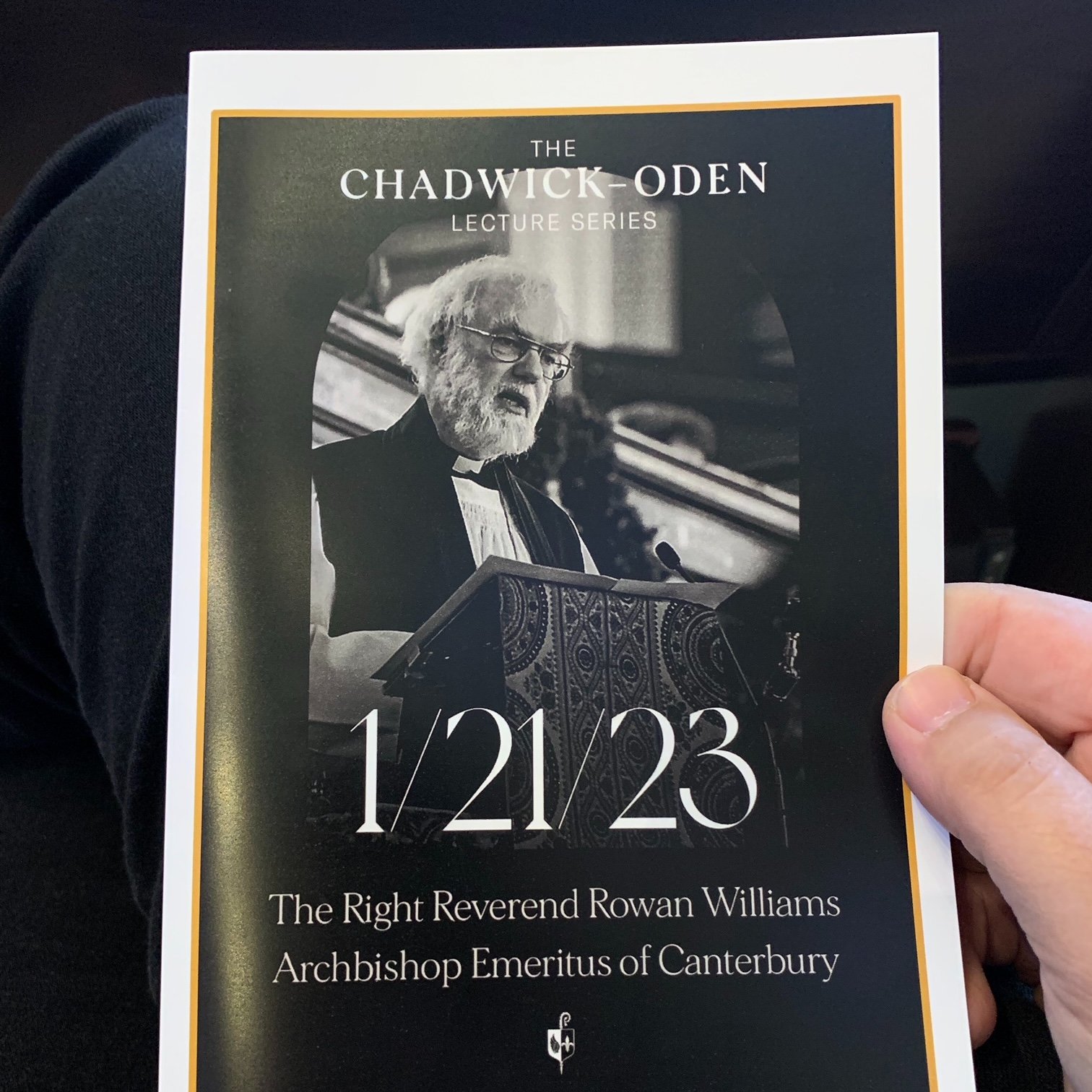

Rowan Williams gave two lectures, inaugurating what is to be known as the Chadwick-Oden series. The morning lecture was based on Augustine’s Confessions and turned our attention inward, reflecting on self-knowledge and memory as they relate to our life with God. Williams invited us to ask questions like this: “Where do I sit in the grand mystery of truth?” The afternoon lecture drew from City of God, and was concerned more broadly with society and the common good. Williams invited us to see ourselves as Augustine does, as the “civitas peregrina”—a pilgrim people with shared commitments that just might bring new life to the world around us.

In attendance that day were a variety of academics, as well as pastors and priests, a bishop or two, the daughter of Augustine scholar Henry Chadwick, a couple dozen white-habited monks, and a billionaire philanthropist couple who had underwritten the whole shebang. During the Q&As, members of this august crowd asked questions I’d characterize (with some exceptions) as solemn, technical, and/or long-winded. Our Welsh lecturer’s responses were, of course, warm, engaging, and full of surprises. One of his answers—getting into the practical outworking of an Augustinian political ethic—involved a personal story about meeting Robert Mugabe, the infamous president of Zimbabwe, who Williams and other Anglican archbishops from the region confronted over human rights abuses.

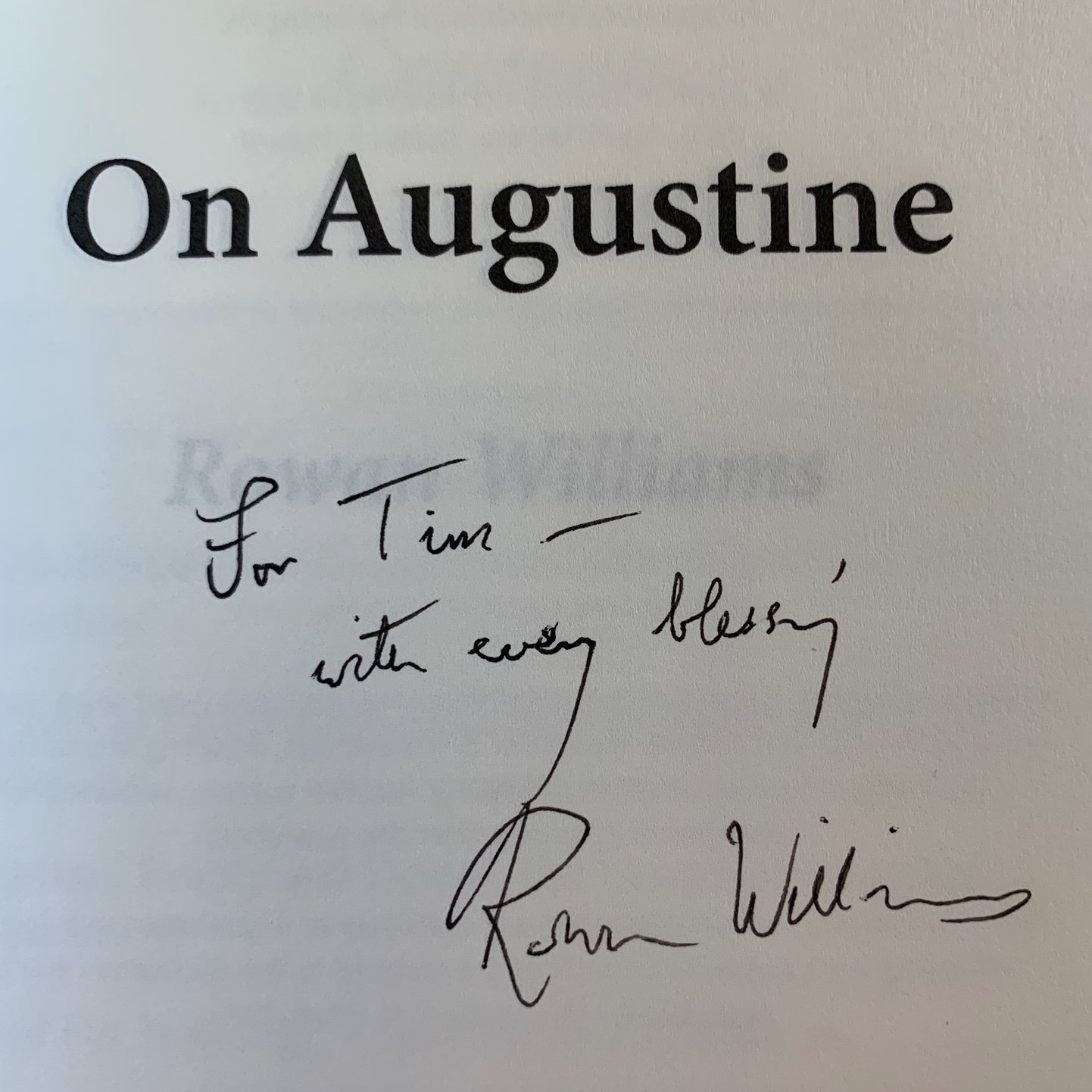

As someone with an abiding interest in Augustine and a deep (if often mystified) appreciation for the writing of Rowan Williams, I was transfixed just about all day. I took feverish notes like a nerd. But as someone who is not a scholar, nor a billionaire philanthropist, nor a monk, I’ll admit to more than a few moments when I felt completely out of place.

At lunch, though, I just so happened to sit down next to a few Jesuits who had driven down from Los Angeles. And as we got to know each other, gradually I felt less alone, like less of an imposter. One of these Jesuits, a professor of cultural anthropology and biblical studies, put his finger on some fascinating dynamics at play in this abbey and new lecture series that I had sensed but had been unable to name. Another, from Malaysia, told me about his forthcoming book on desire and politics in the writing of Augustine and Hannah Arendt. You better believe I’ll be reading that one.

The third Jesuit I met, a priest from the Philippines, has lived and done community development work in a part of Cambodia I visited many years ago. We compared notes about the wounds of war in the countries where the two of us were born and raised, about the subtle and not-so-subtle forces that conspire against remembering, and about how true healing is impossible without it. I told him about the book I hope to write, someday, about all of this. He looked me in the eye and said, “Tim, please write that book.”

I went to the abbey that day to hear a Welshman lecture on Augustine. And yeah, every bit of that was a dream. But driving out of the canyon at the end of the day—listening to a collection of Welsh hymns, including the soul-stirring “Cwm Rhondda”—I was thinking about those Jesuits. I thanked God for their kindness, their generosity of spirit, and for the ways they have found to take lofty theological ideas and translate them into action, in classrooms and slums and wherever else God might lead them.

Augustine, I have to believe, would certainly approve.