5 Things Desmond Tutu Taught Me

It’s a good practice, I think, to read books about inspiring people who have lived remarkable lives. It’s a way of learning to see the world through the eyes of those who have most profoundly shaped it. For my part, I’ve made it a point to learn what I can from Nobel Peace Prize winners – folks like Martin Luther King, Jr., Wangari Maathai, Elie Wiesel, Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, Dag Hammarskjöld, and Mother Teresa.

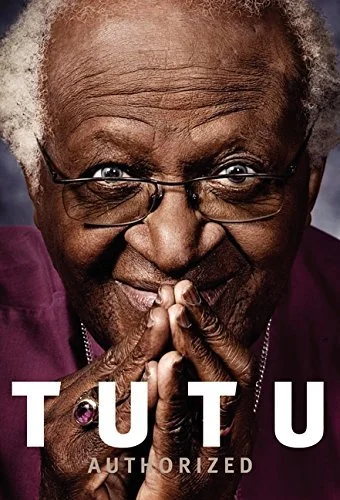

Another remarkably inspiring Nobel laureate for me is Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who led the nonviolent anti-apartheid movement in South Africa and served as chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He just turned 80, and a new biography was published for the occasion: Tutu: Authorized (HarperOne), by South African journalist Allister Sparks and Tutu’s daughter, Mpho Tutu. The book also includes anecdotes and memories from a great variety of people who have known Tutu or have been impacted by him in different ways, and these perspectives give the book its intimate feel. I’d already read two of Tutu’s books, and did some research on him while I was at Eastern University, but reading this new biography was a real treat.

While Tutu holds some theological views I fundamentally disagree with, he’s still someone I look to with tremendous gratitude and respect for all he has done to work for peace and reconciliation as a church leader. I hope he has paved the way for many who will follow in his footsteps. Most of us won’t shape history quite the way Tutu has, but I think all of us can learn from his example and consider the implications for our own spheres of influence, however great or small they may be.

Here are five things about Tutu that jumped out while reading the new biography.

1. Spiritual disciplines: time after time, those reflecting on Tutu’s life referred to the impact of his practice of spending hours every day in silence and prayer. While it could come across as snobbish or holier-than-thou for Tutu to leave a meeting or party or to sit silently in a car ride with a reporter and spend that time praying, no one seems to think he’s a spiritual snob. Rather, they see the rest of his life — the calm, the joy, the perseverance, the humility – and they’re impressed. And many of them, for what it’s worth, don’t share Tutu’s faith.

2. Being fully present: Tutu recognizes that to give to others as he does so deeply and consistently, he needs to be nourished. The flip side of spending so much time alone and in prayer, then, is that when he’s with people, he’s with them fully. And he’s the same person, it seems, whether he’s with long-time friends, with a world leader for the first time, or with an ordinary person like you or me. He seems to have a humanizing effect on people even — or perhaps especially — in dehumanizing situations. This plays out in his belief in ubuntu, which roughly translates into “a person is a person through other people.”

3. Humor: an immensely important but largely overlooked quality among his fellow activists is Tutu’s sense of humor. He never seems to take himself too seriously, and his humor is often self-deprecating. It’s evident that his sense of humor had a lot to do with dispelling a number of quite tense situations during the apartheid era when there wasn’t much to laugh about. By putting his audiences at ease, it made his costly message of peace and reconciliation a lot easier to swallow.

4. Humility: one never gets the sense that Tutu considers himself better than anyone else. He was constantly present with poor, angry black South Africans when it would have been much safer to champion their cause from a distance. He didn’t allow his international fame to go to his head or to distract him from the reality on the ground. Also, when Nelson Mandela was released from prison, Tutu quietly stepped away from his temporary role as political leader of the movement, happy to see someone else take the lead. This kind of humility is beautiful because it is rare.

5. Civility: at a time when pressure was mounting among black South Africans to take up arms against the apartheid government, Tutu did what he could to seek nonviolent alternatives and to urge restraint on both sides. Rather than pitting himself against white South Africans or demonizing them, he sought to show that everyone desperately needed a new way forward. In a world of terrifying religious extremism, Tutu’s civility is a breath of fresh air. While his vision for a “rainbow people of God” and his affirmation of the equal goodness of all religions leads him, in my estimation, into theological relativism and universalism, he has nonetheless led one of the most remarkable nonviolent movements in history — and for that example and legacy we can all be grateful.